The Guardian published an article a couple of weeks ago by Tim Burgess of The Charlatans about the state of the music business in the light of Brexit, streaming and downloads. It’s an interesting read as far as it goes and it set the cogs whirring about why we got here, where we go next and will it be better or worse, or just different.

In my lifetime, the music business has been turned upside down. In the seventies, bands went out on tour to build up a following and to promote singles and albums, which is where the real money was. If you’ve survived this long and remember all this, bear with me, it’s worth getting some historical context. No internet, no mobile phones, only three TV channels and (until October 1973) no commercial radio. So you were left with the pirates like Caroline and the erratic reception of overseas stations like Luxembourg to let you know about new music. And the music press…

Every week I bought the NME, Melody Maker and Sounds and my paper round meant I could sneak a look at Blues & Soul and Disc/Disc and Music Echo as well. By 1973, with a bar job and a Saturday job with an entertainment agent booking acts for local pubs and clubs, I had a few bob to spend on some of the music I was reading about. Add the cost of my print habit to the cost of buying an album (about five percent of the average weekly wage in the mid-seventies) and being into music was a real financial commitment (even if you took the risk of doing a few temporary swaps with your mates to dip into their choices).

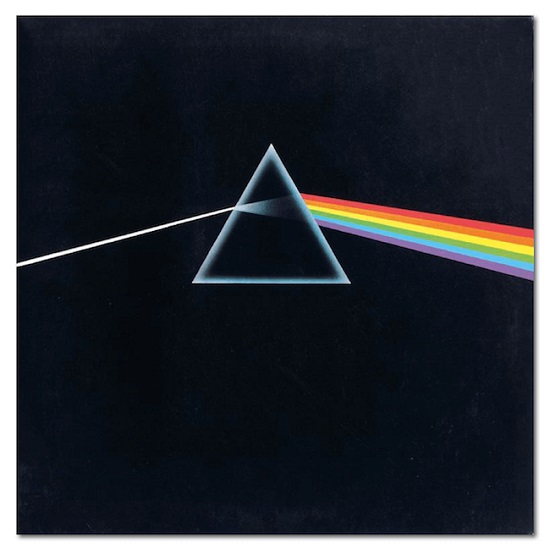

Buying music in the seventies wasn’t just an investment in listening to a piece of music. You exchanged your hard-earned (cash of course) for something physical that you carried home in a bag before lowering it on to the turntable, gently caressing the vinyl with the stylus and waiting for a glorious noise to erupt from the speakers. But let’s just rewind that a few minutes. If you bought an album and you were taking public transport home, you had the chance to look at the album artwork as well. A good album sleeve was so much more than a bit of on-shelf advertising; a twelve-inch square format created opportunities for quality photography and graphic design to enhance the musical content of the package. When it worked, it was an extra visual dimension to a piece of aural art:

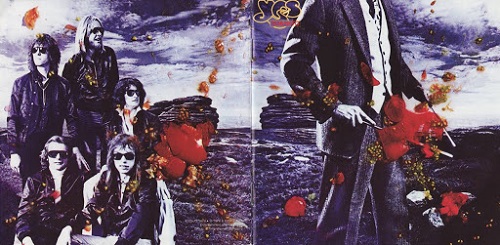

When it didn’t, it looked a lot like this (which proves that you can’t get it right all the time):

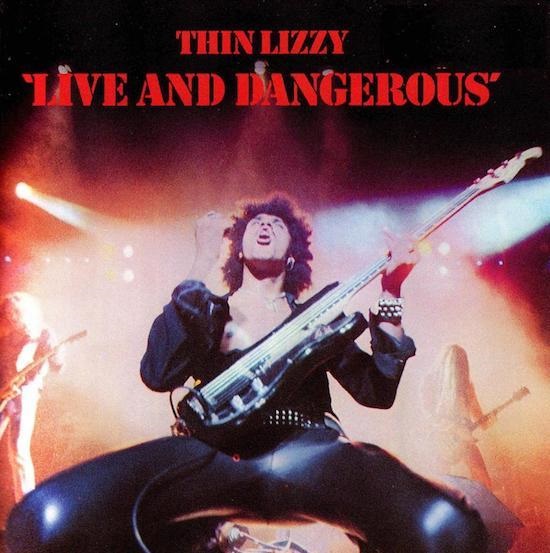

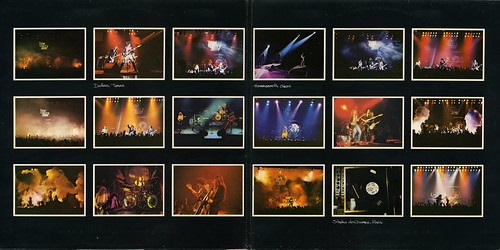

The gatefold sleeve doubled up the visual real estate (exploited perfectly on Thin Lizzy’s “Live and Dangerous” double album with a shedload of Chalkie Davies pics all over the outer and inner sleeves of the album):

Designers started to exploit die-cut sleeves and all sorts of interesting innovations; PiL’s “Metal Box” looked really clever, but only if you hadn’t seen The Small Faces’ “Nut Gone Flake” packaging twelve years earlier.

The visuals were only part of the album experience; you could get a lot of text on a sleeve, particularly if you had a printed inner sleeve or three as well. There was all the obvious geek stuff; musicians involved, instruments played (or not played if you were Queen) and lyric sheets, but some bands made a real effort; UB40’s cover for the first album “Signing Off” in 1980 was a copy of the unemployment benefit attendance card, they’d been filling in before they broke through. Ten years later, Squeeze released a live album with a boxing concept, “A Round and A Bout” with a little bonus – they listed every gig they’d done between 1974 and 1990 on an insert with the album. Thanks guys, you’ve no idea how useful that’s been to me over the years. Seriously.

I’m sure you get the message by now. During the first vinyl era, the experience was about much more than just listening to the music. You could carry an album around at school as a sign of your taste and discernment and to impress the other gender (I pitied the guys who carried Groundhogs and Genesis albums, but that’s Darwinism for you). It was a bit like creating a mixtape a few years later and a playlist many years later. Or drinking bottled designer lager in the eighties. If you were a fan of music in the seventies or eighties you were committed and attached to it; it had a financial and emotional value. And it had a longer lifespan; since the mid-nineties, the norm is for singles and albums to achieve their highest chart position in the first week of release, but fifty years ago the climb to the top of the charts could take weeks (and probably a few bulk purchases in chart return shops to help it along).

This isn’t a dewy-eyed, rose-tinted trip down memory lane. The seventies and eighties weren’t perfect; the music business was still a business, but it was one where labels invested in bands with a view to development over several years. A moderately successful band writing their own material could make a living for a few years with royalties on sales, radio, juke box and club plays and independent labels were few and far between. Things are a bit more polarised these days; the business only supports guaranteed winners and everyone else has to do their own thing. Time for a bit of a polemic: the technology that enabled the digital revolution degraded our experience of music. Listening to compressed audio on inadequate playback systems is the norm for most people now, despite the vinyl comeback, and the majority of listeners don’t pay any attention to artwork, credits or sleeve notes. We’ve walked blindfold into accepting a gradual erosion of the musical experience in the name of progress and fashion. We also have at least one generation that doesn’t believe in physical musical formats and certainly doesn’t believe in paying for them.

Fortunately the same digital technology that devalued music by making no-degradation copying possible, then compression, along with affordable storage and massive improvements in internet bandwidth, have enabled affordable home recording. Technological improvements cut both ways and musicians are a resourceful bunch; if you can’t get a deal with a major label, what have you lost? You don’t need access to a studio; you can set up at home. You don’t need access to a major label’s mastering and pressing facilities; you can find any number of those online. You don’t need a distribution network; you can load your music up to download and streaming services and make peanuts, or you can sell CDs and albums on your website by mail order and alongside other merchandise at your gigs.

In normal times, this isn’t a bad business model; you might be able to stay afloat if you have another job, have good merchandise to sell on tour, or both. And along comes lockdown; no gigs and no pop-up shop opportunities. I wish I could honestly say that I recommended live streams, but it’s not for me; I really miss the eye contact and (selfishly) I miss the opportunity to take pictures at gigs. If it works for you, that’s great; enjoy it and make a contribution; I’ll be waiting for the moment when live music re-emerges after this terrible disease is brought under control.

Me, I’ll continue to avoid the mainstream by buying (in order of preference) vinyl or CDs directly from artists’ websites, from independent record shops and at gigs. Two people I know have opened vinyl shops in the last few years and both are succeeding despite the current trading situation; long may they continue.

And that resourcefulness and creativity that musicians always demonstrate wasn’t going to be stifled by any number of lockdowns; no way. All of those skills developed and equipment bought to set up home studios have been subtly repurposed to enable musicians to collaborate by sharing audio and video files online. I don’t know any musicians who see this as an ideal situation, but, like solitaire, it’s the only game in town. After nearly a year and millions of audio files bouncing around the internet, albums that were in progress have been completed remotely and albums have been conceived, gestated and born. It doesn’t matter how difficult you make life for musicians (or artists generally), they will always find an outlet.

Whenever we reach the new normal, whatever that may be, spend your money in a way that benefits the people making the music you love. Buy physical copies of music either directly from bands or from independent record stores – there are loads of them. Most importantly, get yourself out to as many gigs as possible. I’ll see you at the front.

It’s time to move away from albums, gigs and photos for a while and take a look at some of the music-themed books that have kept me sane on buses, trains and planes during 2015. By sheer chance, I’ve managed to pick out quite a nice variety of styles and themes, so the selection staggers from light-hearted memoirs through serious autobiography to high technology and serious crime (no, I don’t mean the new Coldplay album). So, as ever, in no particular order, here we go.

“How Music Got Free” – Stephen Witt

“How Music Got Free” – Stephen Witt

There’s a myth that’s been perpetuated about the origins of the current situation where we have a generation that won’t pay for music and a generation that doesn’t even recognise the concept of paying for music. What Stephen Witt’s book achieves is a comprehensive demolition of the myth that file-sharing came about because of some sort of people’s revolution where millions of like-minded people decided to share their digital music collections. This well-researched work picks out the various converging paths ultimately leading to the digital devaluation of music. The book explores the bureaucracy that bedevilled the adoption of a standard compression algorithm, the greed of the major music labels as they rushed into the highly lucrative CD market, the failure of the majors to react to the phenomenon of file compression (and increasing online transfer speeds which made sharing a viable proposition) and the outright criminality involved in stealing and counterfeiting masters from CD pressing plants. It’s a fascinating but ultimately depressing book.

“Detroit 67: The Year that Changed Soul” – Stuart Cosgrove

“Detroit 67: The Year that Changed Soul” – Stuart Cosgrove

Stuart Cosgrove has picked out a pivotal year in the history of Motown and imposed a structure of a chapter per month (it works pretty well) which sets the upheavals at Motown against a backdrop of riots in Detriot, unrest in the police force and a general national malaise. Berry Gordy plays a central role in the well-known story of Diana Ross’s advancement at the expense of the other Supremes (and the expulsion of Florence Ballard), but Stuart Cosgrove delves deeper into the sickness at the heart of the company, dealing with the unease of major artists and the ultimate defection of the Holland/Dozier/Holland writing/production team. The book goes far beyond music biography by showing these events in the context of a city in meltdown with riots on either side of the racial divide and a brutal, corrupt police force fanning the flames. It’s a fascinating read, although there are far too many typos in the Kindle edition.

“Fortunate Son” – John Fogerty

“Fortunate Son” – John Fogerty

Confession time: the first song I performed in public was Creedence’s “Up Around the Bend” in a school band which included some good musicians and a future nuclear physicist, and me. I was a fan from an early age. “Fortunate Son” is John Fogerty’s attempt to put the record straight after accusations and counter-accusations, suits and counter-suits with his former band members Doug Clifford and Stu Cook. The book is unflinchingly honest throughout; John Fogerty isn’t trying a whitewash here. He owns up to his mistakes and errors of judgement and this gives him the right to expose others’ lies and hypocrisy. It’s difficult not to empathise with him in his battles with Saul Zaentz and the former Creedence members: he wrote the songs, after all. “Fortunate Son” pivots around John Fogerty’s meeting with his second wife, Julie, who brought order to his chaotic life and pushed him back towards popular and critical recognition. It’s good, it’s honest, it’s straightforward and it’s delivered in an authentic John Fogerty voice.

“Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink” – Elvis Costello

“Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink” – Elvis Costello

Declan McManus has an awful lot of stories to tell and, not surprisingly, he has a gift for writing and storytelling. “Unfaithful Music…” is a cracking read, giving an insight into the creation of some wonderful music, and life in the music business bubble. The book doesn’t follow a straightforward chronological structure; it’s much more like a conversation in the pub with each observation triggering another digression. There are some difficult events to deal with (the Stephen Stills/Ray Charles incident for example) and they’re all dealt with in a very matter of fact way. The book skips over some big chunks of Elvis Costello’s life, but the ones he does tackle are done with honesty and candour. The names that crop up as the story unfolds are a history of popular music, but this never feels like name-dropping, they’re just people who happen to have been around at certain times. This is a wonderful book.

“ Rock Stars Stole My Life” – Mark Ellen

Rock Stars Stole My Life” – Mark Ellen

Mark Ellen’s memoir is a breezy and self-deprecating run through a life as a pop journalist, radio presenter, TV presenter and publisher. He gives an inside view on life at the NME in the seventies, The Old Grey Whistle Test and the Live Aid broadcast, all delivered in a jaunty style that’s very easy to read. He’s met and worked with some amazing people (again, it’s all matter-of-fact rather than name-dropping), but being a member of Ugly Rumours with Tony Blair takes some beating. Most of the book is fairly gentle humour, smiles rather than guffaws, but Mark Ellen saved the best for last. His account of the mayhem aboard Rihanna’s ill-conceived and farcical round-the-world-in-seven-days tour made me laugh out loud. The entire book’s funny, but this piece was hilarious.

If you don’t see anything you fancy there, Chrissie Hynde’s “Reckless” and Bob Harris’s “Still Whispering After All These Years” are both well-written and interesting biographies.

I was just drinking my cocoa and keeping up with all the modern trends in music by watching Jools Holland’s “Later” programme last night when I saw something so disturbing that I almost wrote to “Points of View”. On stage, straight after the wonderful Burt Bacharach, were two badly-dressed Northerners with a stolen laptop balanced on a beer barrel and a beer crate ranting, swearing and shouting over the top of what I think they call ‘beats’ these days. My first reaction was (I’ve been dying to try this out) ‘WTF?’ That actually felt quite good, swearing without really swearing. It might just catch on.

Sorry, bit distracted there. The more I watched, the more horrified I became. Why on earth did Mr Holland have two ill-dressed extras from “This is England” on his show ranting and drinking beer (which is very unprofessional on stage, I must say) alongside his usual smorgasbord of high quality modern musicians? At least the Happy Mondays played proper instruments and had something resembling tunes.

So it must be some kind of performance art then or some elaborate joke. Was it a pair of drama students satirising the quality of modern pop music by creating something so obnoxious and unmusical that it was totally unlistenable and then setting out to see how many people they could con. Or maybe it was the media; someone saw an absolutely terrible pair of hip-hop or post-punk, or whatever they are, performers and decided to play the ‘Emperor’s new clothes’ game; tell them how good they are and then build them up in the music press. If you do that for long enough, one of the inkies will pick up the story and bearded Hoxton types will be saying how they loved their earlier work. Amazingly enough, they’ve been doing this for eight years, apparently. The NME does this sort of thing all the time; how do you think Pete Doherty got away with it for so long.

And talking about the NME, what on earth happened to that? I had one thrust into my hand at the railway station the other day; it’s free these days, so I thought I’d check which giants of modern music they were featuring. There was a piece on drug cartels that could have been researched using Wikipedia and the “Ladybird Book of Crack and Cocaine”, the famous music journalist Katherine Ryan (really) writing about Piggate and MeghanTrainor and a six-page plug for the resurrection of Chis Moyles. Just remember that NME used to stand for New Musical Express and this is someone who can get away with playing three songs in an hour. There was once a time when the NME had writers who were vicious, opinionated, clannish and supercilious but at least it was worth reading; I don’t think those days are ever coming back.

But what about Sleaford Mods, you say? They’re not from Sleaford and I’m sure Mr Weller wouldn’t approve of their version of mod couture and they still look like the people I pass every morning waiting for the off-licence to open. I wonder what that lovely Mr Bacharach made of it?

By the way does anyone know of a good product for cleaning cocoa stains off a carpet?

![220px-Ssilverstein[1]](http://musicriot.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/220px-Ssilverstein1-211x300.jpg) How did I discover Shel Silverstein? Easy, I bought a copy of the Dr Hook and the Medicine Show album “The Ballad of Lucy Jordon” (a contractual obligation “greatest hits” package put together by CBS before the band departed to Capitol and commercial success). As an introduction to early ‘70s Dr Hook, it’s a belter. Released in 1975, it was obviously a vinyl album; you remember those, don’t you? I bought it on the strength of the chart hit “Sylvia’s Mother”, but that wasn’t even close to being the best song on the album; that’s at the end of the album and the end of the next paragraph.

How did I discover Shel Silverstein? Easy, I bought a copy of the Dr Hook and the Medicine Show album “The Ballad of Lucy Jordon” (a contractual obligation “greatest hits” package put together by CBS before the band departed to Capitol and commercial success). As an introduction to early ‘70s Dr Hook, it’s a belter. Released in 1975, it was obviously a vinyl album; you remember those, don’t you? I bought it on the strength of the chart hit “Sylvia’s Mother”, but that wasn’t even close to being the best song on the album; that’s at the end of the album and the end of the next paragraph.

A quick look at the album sleeve showed that fifteen of the sixteen songs were written by someone called Shel Silverstein, who wasn’t even a member of the band, and they were a fascinating collection of songs, ranging from the country pastiche of “The Wonderful Soup Stone” through the Rabelaisian comedy of “(Freaking at) the Freakers’ Ball” and “Roland the Roadie and Gertrude the Groupie” to the superb ( and much-covered) story of a suburban breakdown, “The Ballad of Lucy Jordon”. If you don’t listen to anything else picked out in this piece, you really should listen to the Marianne Faithfull version of this song.

I know this is a nostalgia piece, but there are a lot of things that weren’t better in the old days. In the 21st century, you can find out almost everything about a group or artist within seconds; you can get a biography, you can listen to their material (released and unreleased), you can probably get a message to them directly and they might even reply. In the mid-to-late 70s, you had NME, Sounds, Melody Maker, John Peel and some independent record shops to let you know what was going on. Although I was only really interested his music, I discovered that there was much more to Shel Silverstein than songs; he was also a gifted cartoonist, poet, screenwriter author of childrens’ books.

Eventually, I managed to track down a couple of imported albums (“Songs and Stories” from 1978 and “The Great Conch Train Robbery” from 1980). While the albums didn’t have the polish of the Dr Hook material, they covered a lot of the same territory and gave the impression that once Shel had an idea he had to get it down and move on quickly because there were ten more ideas banging on the door behind it. I loved “Songs and Stories”, from the sheer silliness of “Goodnight Little House Plant”, “Someone Ate the Baby” and “Never Bite a Married Woman on the Thigh” through “The Father of a Boy Named Sue” (he also wrote “A Boy Named Sue”) to the epic stoner poem “The Smoke-Off” and the ode to cop-outs, “They Held Me Down”. It had all the manic energy of a live performance by Robin Williams, who was just emerging as a stand-up at the time.

Shel Silverstein was that rare example of genuine Renaissance Man; he had gifts ranging across the field of creative arts, but it was as a songwriter (and ramshackle, shambolic performer) that I love his work. His serious work, such as “The Ballad of Lucy Jordon” was superb, but he also wrote comedy songs that were actually funny ( I still laugh out loud at the lines: ‘Everybody ballin’ in batches, pyromaniacs strikin’ matches’ from “Freakin’ at the Freakers’ Ball”) and you could bear to listen to more than once. It helped that he drew a lot of his humour from the fringes of society and legality, which gave it an extra frisson to anyone looking in to that world from the outside.

You rarely hear Shel Silverstein’s name mentioned these days, which is a shame, but he has left a huge legacy in print and in music. If you’re still not convinced, just ask yourself what these songs have in common: “A Boy Named Sue”, “Queen of the Silver Dollar”, Sylvia’s Mother”, “25 Minutes to Go” and “Daddy What If”? Yep, all written by Shel Silverstein. Most songwriters would kill to have written any one of those songs, and that’s before you even get to “The Cover of the Rolling Stone” and the sadly under-rated “Last Mornin’”. He’ll make you laugh and he’ll make you cry, but he’ll never bore you.

Ok, NME, you’ve got some explaining to do and, no, it’s not about your obsession with Pete Doherty’s appetite for self-destruction this time. I bought the NME when it was New Musical Express and the emphasis used to be on new. Actually, to be completely fair, it still does new music and too much of it if you ask me. Every week there are at least twenty “great” new bands from around the world featured in “Radar”; that’s a thousand bands a year to feel guilty about not hearing, and that’s not counting the twenty “essential” new tracks featured in “On Repeat”. There is such a thing as too much music. But maybe I just slipped off-topic there for a second.

This might surprise you, coming from a cantankerous old git, but what’s the deal with all the old music in the “New” Musical Express. Apart from the regular features, “Anatomy of an (old) Album”, “Soundtrack of my Life” (old songs) and “This week in …” (old news), the cover features for the last two weeks have been twentieth anniversary pieces on “The Holy Bible” and “Definitely Maybe”. I’m not saying they’re bad albums; they’re not. I parted with my hard-earned for both of them – twenty years ago. So, apart from the front cover, each of these albums gets ten pages in the magazine as well. If you delve further into the back issues, there’s a fairly predictable 100 most influential artists piece (early August) and a Led Zeppelin retrospective (late May).

This is editorial content by focus group and the group must have been fifty per cent Hoxton and Dalston scenesters and fifty per cent old rockers from The Borderline and The 100 Club; sounds like a really bad sixtieth birthday party. So, what’s the target demographic (or whatever the current marketing phrase is for the people you want to buy your product) for big pieces about old music? Is it the Moss-thin, leather shrink-wrapped, pony-tailed Nick Kent wannabe who never stopped reading the New Musical Express, or is it the student who’s waded through all of the new bands and new songs and decided that there’s nothing there worth bothering with and it’s time to start looking back twenty years to find something decent. Can you imagine looking back from 1976 and thinking that you needed to find out a bit more about Pat Boone, Doris Day and Winifred Atwell? Thought not.

So, where do you draw the line? How many more “classic” album anniversaries can we dig out to fill a cover and ten pages that should really be devoted to new music? And what anniversaries do we have lined up over the next few weeks; Crash Test Dummies’ “God Shuffled his Feet”? We could get ten pages out of the (not very) subtle reference to right-wing poster girl Ayn Rand’s novel, “Atlas Shrugged”, and maybe an interview with Neil Peart to pad it out. How about Echobelly’s “Everyone’s Got One”? That got them a whole season on student summer ball circuit before they imploded; should be worth a few pages, and Sonya Madan’s back out there again so she should be happy to get the publicity. Where do you draw the line? Sleeper, Menswear, Lush, Gene? I think you get the picture.

NME, get a grip. If I want to act my musical age, I’ll buy Q or Mojo. Until then, I expect you to tell me about what’s happening now, not twenty years ago.

What is it with NME and Pete Doherty (and Carl Barat)? It’s bad enough that they insist on force-feeding us his incoherent ramblings and telling us about the latest way he’s found of shortening his life but, come on, an NME cover and a six-page feature about the reasons for reforming for the Hyde Park gig. We know the reasons, and there are about five hundred thousand of them; it’s not a news story. But seriously, a cover and six pages; surely music fans in 2014 don’t even care about Pete Doherty any more, but for some reason he’s always been the darling of the NME, no matter what he does. I mean they even picked him in a taxi after one of his spells at Her Majesty’s for an exclusive interview. I should be more disappointed when the inkies fall for it as well, but who buys the Grauniad or the Torygraph for their music reviews?

The Libertines had a couple of good songs over a decade ago and the NME have been trying to sanctify Pete Doherty ever since; we really don’t care and neither should they. Maybe they just like to be seen hanging around with the bad boys; it wasn’t cool when Nick Kent did it and it’s still not cool now. I don’t care what he does to his own body but I do care when journalists think that “I’ve seen Pete Doherty taking drugs” is a story that we all need to read. This is a man who once described crack as “a bit moreish”, tongue-in-cheek, maybe, but still pretty dim. What’s the attraction of someone who is willing to steal his own bandmate’s laptop to sell for drugs? It’s not exactly sticking it to the man is it? But it’s made so much worse by NME writers glorifying his every action.

So how do they actually fill six pages with this story? Well, a full-page posed photo and a banner headline take up two pages before Matt Wilkinson describes how he spent an entire day on the phone to members of the band. While he was speaking to the NME idol, Doherty put the phone down and started to spontaneously work on a new song which, predictably, “sounds fantastic”. You two should really get a room, Matt. I’m not sure how the devoted Libertines fans feel about this, but at least Pete Doherty is honest about the motivation for the reunion and he defends the band’s right to do the Hyde Park gig for the money.

The NME also demonstrates the internal conflict at the magazine by asking two journalists to give opposing views on whether the Hyde Park gig is a good idea; unsurprisingly, both of them love the Libertines. Tom Howard thinks they should do it although it might be pants (or not perfect). Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but if I’m paying to see a gig, my minimum expectation is that the band can actually play the songs, and that’s the bare minimum. But it gets better; Jenny Stevens doesn’t want them to play and tries to convince us of the Libertines’ working-class credentials and solidarity with the workers; Pete Doherty’s dad was a major in the British army and that’s a long way from growing up on a council estate. Pete Doherty chose to be a waster while hundreds of thousands of genuine working class kids worked and studied and made a genuine contribution to society. So don’t try to sell me that spurious social solidarity routine. And can you really imagine Pete Doherty killing a man for his Giro?

If the members of The Libertines insist on repeatedly resurrecting the rotting cadaver of their band and punters are gullible enough to shell out £50 for a shoddy show, then let them get on with it but I can live without the NME giving its blessing to the whole process. There are probably dozens of good bands playing in London on July 5th, go and watch one of them instead.

Ok, call me obsessive if you like but as well as listening to a lot of albums and going to as many gigs as I can, I also read the odd book or two about music and popular culture and many of those are worth sharing with anyone who checks out MusicRiot regularly. This list was difficult to pin down to five from the start, but it became even more difficult on Christmas Day when I was given a copy of the Donald Fagen memoir/tour diary/article compilation, “Eminent Hipsters”. So I guess that’s a pretty good place to start.

“Eminent Hipsters” – Donald Fagen

Where do I start with Donald Fagen? With Walter Becker, he was half of one of my favourite 70s bands, Steely Dan and then went on to release the classic solo album, “The Nightfly” in 1982, followed (not too closely) by “The Kamakiriad” in 1993. You’ve probably guessed by now, I’m a bit of a fan. “Eminent Hipsters” is partly an explanation, through a series of articles, of the factors which influenced the Steely Dan sound (cool jazz, cop dramas and wise-ass comedians) and the Donald Fagen solo sound (science fiction and mid-century paranoia). If you love the music, you’ll be fascinated by these observations about its roots. The second part of this slim volume is devoted to Fagen’s diary from the 2012 “Dukes of September Rhythm Revue” tour which is, by turn, snarky, moving, insightful and downright hilarious.

Where do I start with Donald Fagen? With Walter Becker, he was half of one of my favourite 70s bands, Steely Dan and then went on to release the classic solo album, “The Nightfly” in 1982, followed (not too closely) by “The Kamakiriad” in 1993. You’ve probably guessed by now, I’m a bit of a fan. “Eminent Hipsters” is partly an explanation, through a series of articles, of the factors which influenced the Steely Dan sound (cool jazz, cop dramas and wise-ass comedians) and the Donald Fagen solo sound (science fiction and mid-century paranoia). If you love the music, you’ll be fascinated by these observations about its roots. The second part of this slim volume is devoted to Fagen’s diary from the 2012 “Dukes of September Rhythm Revue” tour which is, by turn, snarky, moving, insightful and downright hilarious.

Donald Fagen writes in an instantly-identifiable style betraying a debt to Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, which sneaks in when describing Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” as getting :”out of that cab on Fifth Avenue in a black dress and pearls in the early morning, I wanted to sip her through a straw”. It’s beautifully written and you can get through it in a few hours; it takes 170 pages to deliver a message that most rock biographies take at least five times as long to get over.

“Bedsit Disco Queen: How I Grew Up and Tried to be a Pop Star” – Tracey Thorn

If Donald Fagen’s prose style is easily identifiable, then Tracey Thorn’s is even more so. I’m always impressed when musicians get this right (Peter Hook and Luke Haines also do it particularly well) and, from the first paragraph, this is pitch-perfect ‘Popstar Trace’. The book takes us from the Marine Girls beginnings through the EBTG false starts and eventual success to the beautiful Massive Attack vocals (I’m biased, but you should read about the origins of the modern classic, “Protection” here) and the worldwide Todd Terry-remixed success of “Missing”.

If Donald Fagen’s prose style is easily identifiable, then Tracey Thorn’s is even more so. I’m always impressed when musicians get this right (Peter Hook and Luke Haines also do it particularly well) and, from the first paragraph, this is pitch-perfect ‘Popstar Trace’. The book takes us from the Marine Girls beginnings through the EBTG false starts and eventual success to the beautiful Massive Attack vocals (I’m biased, but you should read about the origins of the modern classic, “Protection” here) and the worldwide Todd Terry-remixed success of “Missing”.

Tracey’s style is perfectly self-deprecatory; you never feel a hint of false modesty and the mentions of famous musicians are always very matter-of-fact, including the story about waiting to pick the kids up from school and being shouted at by George Michael from a Range Rover. This is a wonderful memoir from a genuine pop star.

“Yeah, Yeah, Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop” – Bob Stanley

It’s obvious from the outset that this is actually a companion piece to the classic 2012 St Etienne album, “Words and Music”. The album was a voyage through the history of British pop music and the book is an extended verbal remix of the ground covered by the album. What’s equally obvious is that Bob Stanley is both an enthusiast and an insider, which gives him a unique perspective on his subject. He aims to show the links between different styles using not just the music, but also sociological and technological developments. If you’re interested in the history of pop music and you’ve done a bit of research, you might disagree with some of his pronouncements, but it’s a big book and you’ll probably agree with ninety per cent of them.

It’s obvious from the outset that this is actually a companion piece to the classic 2012 St Etienne album, “Words and Music”. The album was a voyage through the history of British pop music and the book is an extended verbal remix of the ground covered by the album. What’s equally obvious is that Bob Stanley is both an enthusiast and an insider, which gives him a unique perspective on his subject. He aims to show the links between different styles using not just the music, but also sociological and technological developments. If you’re interested in the history of pop music and you’ve done a bit of research, you might disagree with some of his pronouncements, but it’s a big book and you’ll probably agree with ninety per cent of them.

The book takes the first NME chart in 1952 as its starting point (which is logical and not controversial) and the end of vinyl as a chart force in 1993 as its end point, when the first Number One singles not to have been released as a 7” single or (a few months later) on vinyl at all topped the charts (if you want to know what they are, you can buy the book ). It’s a slightly more controversial choice but still with a logical basis for someone who grew up in the age of vinyl. The book has an authority derived from Bob Stanley’s experience as a writer and member of a very successful pop group but never slips into the socio-cultural academic approach of, for example, Simon Reynolds. The theme that underpins everything else in this book is that Bob Stanley is still a fan who wants you to come round and listen to his records, and that makes this an unmissable book.

“Here Comes Everybody: The Story of the Pogues” – James Fearnley

I’ve always been a fan of the “inside story” biography, particularly those that aren’t ghost-written attempts at cultural revisionism. This memoir by James Fearnley is, at times, brutally and crushingly honest about members of The Pogues and he doesn’t spare himself either. The book begins by setting the scene with Shane MacGowan’s departure from the band in 1991 before moving back to Fearnley’s initial meeting with MacGowan at an audition for The Nips in 1980.

I’ve always been a fan of the “inside story” biography, particularly those that aren’t ghost-written attempts at cultural revisionism. This memoir by James Fearnley is, at times, brutally and crushingly honest about members of The Pogues and he doesn’t spare himself either. The book begins by setting the scene with Shane MacGowan’s departure from the band in 1991 before moving back to Fearnley’s initial meeting with MacGowan at an audition for The Nips in 1980.

The book is a (mainly) unsentimental account of the rise and fall of The Pogues from the viewpoint of someone close enough to see everything but with enough distance to retain some objectivity. From the chaotic managerless beginnings through the unpopular but successful stewardship of Frank Murray, the story is underpinned at all times by MacGowan’s unpredictability and seemingly random self-destructive urges. James Fearnley tries very hard to balance the singer’s inexcusable behaviour against the genius of the songs, but it’s up to you if you buy that line; I certainly don’t. My only criticism is that James Fearnley spends a little too much time trying to emphasise the fact that he’s a writer and occasionally introduces unnecessarily florid prose to prove it; putting that aside, it’s still a winner.

“Sounds like London: 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital” – Lloyd Bradley

Bear with me for a minute here; this will all make sense presently. Earlier this year I read “How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and the Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005” by Richard King. It’s a very good book and a must for geeks like us, but it attracted a lot of criticism because it didn’t touch on the black music scene. Richard King was even accused, pathetically, of racism in some quarters; you might even have read about it. Personally, I prefer to read authors who write about subjects they understand and that really inspire them; if Richard King didn’t have the expertise, contacts or inspiration to write about the black music scene, then Lloyd Bradley certainly did.

Bear with me for a minute here; this will all make sense presently. Earlier this year I read “How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and the Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005” by Richard King. It’s a very good book and a must for geeks like us, but it attracted a lot of criticism because it didn’t touch on the black music scene. Richard King was even accused, pathetically, of racism in some quarters; you might even have read about it. Personally, I prefer to read authors who write about subjects they understand and that really inspire them; if Richard King didn’t have the expertise, contacts or inspiration to write about the black music scene, then Lloyd Bradley certainly did.

The title is a little misleading; there’s very little about pre-1950s black music, and it also deals with regional English offshoots from the London scene but those aren’t criticisms, just observations. The reason for the comparison with Richard King’s book is that one of Lloyd Bradley’s recurring themes is that black British music has always developed and prospered healthily out of the mainstream when produced and distributed independently.

Once the book reaches the point where Lloyd Bradley can introduce interviews with the players who made black British music happen (the steel pan players, the jazzers, the sound system pioneers, the Britfunk players and the mainstream crossovers Eddy Grant, Janet Kay, Jazzie B and the rest), the narrative really takes off with stories of the sound systems and records being sold out of the back of a car and distributed around the country in the same way. Lloyd Bradley takes us through calypso, ska, reggae, lovers rock, dub, britfunk, 98 bpm, trip hop, jungle, d’n’b, UK garage, dubstep and grime along with a host of short-lived one-way streets with an unassuming and easy authority that is very seductive. If you want an introduction to black British music, this is the book for you.

OK, spoilers alert; I’ve relented. I’ll tell you that the chart-toppers Bob Stanley refers to in 1993 and 1995 respectively are Culture Beat’s “Mr Vain” and Celine Dion’s “Think Twice”, but you should still read the book. Actually you should read all of these books.