The Guardian published an article a couple of weeks ago by Tim Burgess of The Charlatans about the state of the music business in the light of Brexit, streaming and downloads. It’s an interesting read as far as it goes and it set the cogs whirring about why we got here, where we go next and will it be better or worse, or just different.

In my lifetime, the music business has been turned upside down. In the seventies, bands went out on tour to build up a following and to promote singles and albums, which is where the real money was. If you’ve survived this long and remember all this, bear with me, it’s worth getting some historical context. No internet, no mobile phones, only three TV channels and (until October 1973) no commercial radio. So you were left with the pirates like Caroline and the erratic reception of overseas stations like Luxembourg to let you know about new music. And the music press…

Every week I bought the NME, Melody Maker and Sounds and my paper round meant I could sneak a look at Blues & Soul and Disc/Disc and Music Echo as well. By 1973, with a bar job and a Saturday job with an entertainment agent booking acts for local pubs and clubs, I had a few bob to spend on some of the music I was reading about. Add the cost of my print habit to the cost of buying an album (about five percent of the average weekly wage in the mid-seventies) and being into music was a real financial commitment (even if you took the risk of doing a few temporary swaps with your mates to dip into their choices).

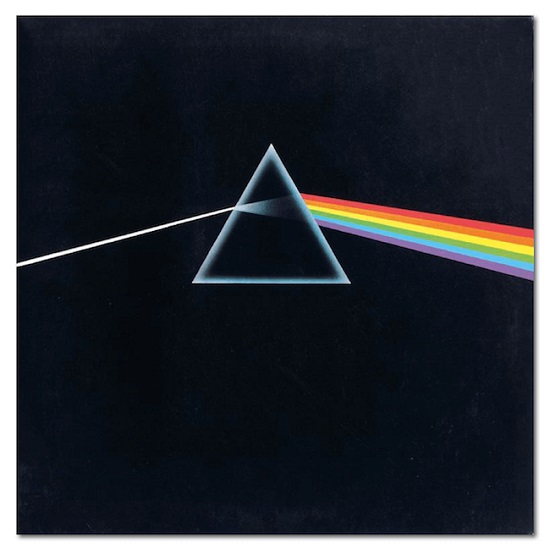

Buying music in the seventies wasn’t just an investment in listening to a piece of music. You exchanged your hard-earned (cash of course) for something physical that you carried home in a bag before lowering it on to the turntable, gently caressing the vinyl with the stylus and waiting for a glorious noise to erupt from the speakers. But let’s just rewind that a few minutes. If you bought an album and you were taking public transport home, you had the chance to look at the album artwork as well. A good album sleeve was so much more than a bit of on-shelf advertising; a twelve-inch square format created opportunities for quality photography and graphic design to enhance the musical content of the package. When it worked, it was an extra visual dimension to a piece of aural art:

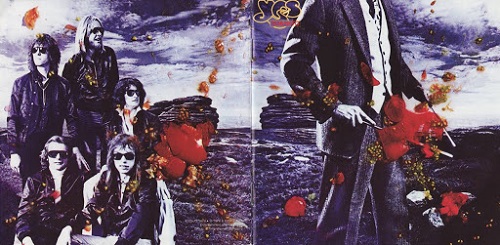

When it didn’t, it looked a lot like this (which proves that you can’t get it right all the time):

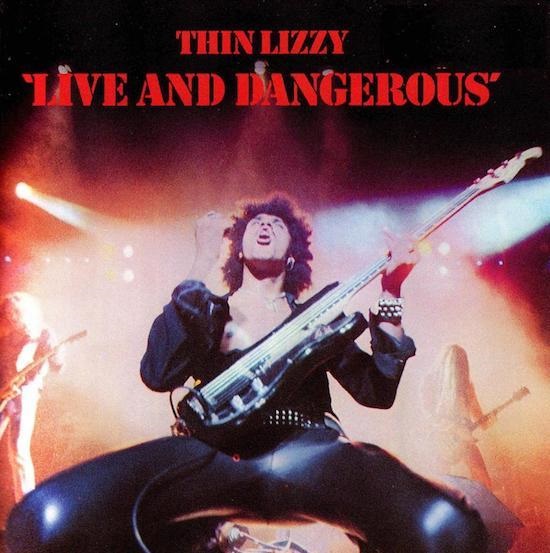

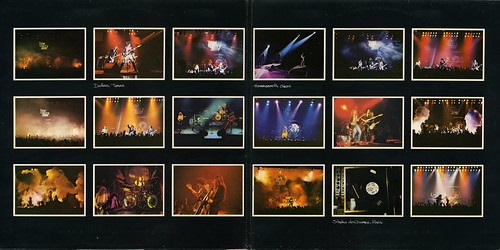

The gatefold sleeve doubled up the visual real estate (exploited perfectly on Thin Lizzy’s “Live and Dangerous” double album with a shedload of Chalkie Davies pics all over the outer and inner sleeves of the album):

Designers started to exploit die-cut sleeves and all sorts of interesting innovations; PiL’s “Metal Box” looked really clever, but only if you hadn’t seen The Small Faces’ “Nut Gone Flake” packaging twelve years earlier.

The visuals were only part of the album experience; you could get a lot of text on a sleeve, particularly if you had a printed inner sleeve or three as well. There was all the obvious geek stuff; musicians involved, instruments played (or not played if you were Queen) and lyric sheets, but some bands made a real effort; UB40’s cover for the first album “Signing Off” in 1980 was a copy of the unemployment benefit attendance card, they’d been filling in before they broke through. Ten years later, Squeeze released a live album with a boxing concept, “A Round and A Bout” with a little bonus – they listed every gig they’d done between 1974 and 1990 on an insert with the album. Thanks guys, you’ve no idea how useful that’s been to me over the years. Seriously.

I’m sure you get the message by now. During the first vinyl era, the experience was about much more than just listening to the music. You could carry an album around at school as a sign of your taste and discernment and to impress the other gender (I pitied the guys who carried Groundhogs and Genesis albums, but that’s Darwinism for you). It was a bit like creating a mixtape a few years later and a playlist many years later. Or drinking bottled designer lager in the eighties. If you were a fan of music in the seventies or eighties you were committed and attached to it; it had a financial and emotional value. And it had a longer lifespan; since the mid-nineties, the norm is for singles and albums to achieve their highest chart position in the first week of release, but fifty years ago the climb to the top of the charts could take weeks (and probably a few bulk purchases in chart return shops to help it along).

This isn’t a dewy-eyed, rose-tinted trip down memory lane. The seventies and eighties weren’t perfect; the music business was still a business, but it was one where labels invested in bands with a view to development over several years. A moderately successful band writing their own material could make a living for a few years with royalties on sales, radio, juke box and club plays and independent labels were few and far between. Things are a bit more polarised these days; the business only supports guaranteed winners and everyone else has to do their own thing. Time for a bit of a polemic: the technology that enabled the digital revolution degraded our experience of music. Listening to compressed audio on inadequate playback systems is the norm for most people now, despite the vinyl comeback, and the majority of listeners don’t pay any attention to artwork, credits or sleeve notes. We’ve walked blindfold into accepting a gradual erosion of the musical experience in the name of progress and fashion. We also have at least one generation that doesn’t believe in physical musical formats and certainly doesn’t believe in paying for them.

Fortunately the same digital technology that devalued music by making no-degradation copying possible, then compression, along with affordable storage and massive improvements in internet bandwidth, have enabled affordable home recording. Technological improvements cut both ways and musicians are a resourceful bunch; if you can’t get a deal with a major label, what have you lost? You don’t need access to a studio; you can set up at home. You don’t need access to a major label’s mastering and pressing facilities; you can find any number of those online. You don’t need a distribution network; you can load your music up to download and streaming services and make peanuts, or you can sell CDs and albums on your website by mail order and alongside other merchandise at your gigs.

In normal times, this isn’t a bad business model; you might be able to stay afloat if you have another job, have good merchandise to sell on tour, or both. And along comes lockdown; no gigs and no pop-up shop opportunities. I wish I could honestly say that I recommended live streams, but it’s not for me; I really miss the eye contact and (selfishly) I miss the opportunity to take pictures at gigs. If it works for you, that’s great; enjoy it and make a contribution; I’ll be waiting for the moment when live music re-emerges after this terrible disease is brought under control.

Me, I’ll continue to avoid the mainstream by buying (in order of preference) vinyl or CDs directly from artists’ websites, from independent record shops and at gigs. Two people I know have opened vinyl shops in the last few years and both are succeeding despite the current trading situation; long may they continue.

And that resourcefulness and creativity that musicians always demonstrate wasn’t going to be stifled by any number of lockdowns; no way. All of those skills developed and equipment bought to set up home studios have been subtly repurposed to enable musicians to collaborate by sharing audio and video files online. I don’t know any musicians who see this as an ideal situation, but, like solitaire, it’s the only game in town. After nearly a year and millions of audio files bouncing around the internet, albums that were in progress have been completed remotely and albums have been conceived, gestated and born. It doesn’t matter how difficult you make life for musicians (or artists generally), they will always find an outlet.

Whenever we reach the new normal, whatever that may be, spend your money in a way that benefits the people making the music you love. Buy physical copies of music either directly from bands or from independent record stores – there are loads of them. Most importantly, get yourself out to as many gigs as possible. I’ll see you at the front.

Ok, some life lessons for music lovers from tonight. First, if you get a chance to go and see a band (even on a school night), do it, because life’s too short. Second, when a mate recommends a band, go and see them. Third, the escalator at Angel station is the longest on London Underground and I’m not getting any younger; running up any escalator is for the young and fit, as I discovered. So, pulling all of this together, my mate Paul in Middlesbrough (closely followed by Graeme Wheatley from The Little Devils) told me I should have a look at The Jar Family, who were playing at The Islington.

Ok, some life lessons for music lovers from tonight. First, if you get a chance to go and see a band (even on a school night), do it, because life’s too short. Second, when a mate recommends a band, go and see them. Third, the escalator at Angel station is the longest on London Underground and I’m not getting any younger; running up any escalator is for the young and fit, as I discovered. So, pulling all of this together, my mate Paul in Middlesbrough (closely followed by Graeme Wheatley from The Little Devils) told me I should have a look at The Jar Family, who were playing at The Islington.

The Jar Family is another example of a group of people who have realised that the music business as we knew it doesn’t exist now. A bunch of players and songwriters from the Hartlepool area decided that the best way to get their songs heard was to work together as one unit drawing on the creative input of all the members. After a lot of hard work and personal sacrifice, they’ve come up with something really special which Teesside has known about for a while and the rest of the country is just beginning to catch up with.

The band members are: Max Bianco (vocals, guitar, harmonica, percussion), Dali (vocals, guitar, slide guitar, percussion), Richie Docherty (vocals, guitar, percussion), Chris Hooks (vocals, lead guitar), Keith Wilkinson (bass, vocals) and Kez Edwards (drums). If that sounds like a lot going on, it’s even busier when you put them on a stage, with the look of a Victorian street gang infiltrated by Tim Burgess. There’s a lot of movement between songs as the three singers take turns centre stage and guitars are swapped around, but it’s smooth and professional in a way that reflects the amount of work they’ve put in over the last few years.

The set opens with the latest single “In the Clouds” and rattles through a mainly uptempo set including “World’s Too Fast”, “Machine”, “In For a Penny”, “Footsteps”, “Paint Me a Picture”, “She Was Crying”, “Moya Moya” and “Tell me Baby” before a two-song encore of “Debt” and the appropriate closing stomper “Have to Go”. There are plenty of committed fans in the audience who have made the journey down from the North-East but by the end of the set, the rest have been won over as well by a combination of a varied bunch of songs delivered in ever-changing instrumental settings by a very tight and solid group of musicians, but that still doesn’t tell the full story of The Jar Family’s appeal and why they’ve built up such a fanatical following so far.

There are a couple of things that single this band out from the crowd. The band members interact with their audience on and off stage in a way that creates a shared experience; this isn’t about us and them, it’s about everyone together. The other thing is the songs; they’re accessible (whether they’re raucous or quietly melodic) and the lyrics deal with themes that most of us can relate to our daily lives. When you put a group of people like us on stage singing songs that could be about us, it’s a difficult combination to resist, particularly when the vocal and instrumental performances are so good. I understand what all the fuss is about now.