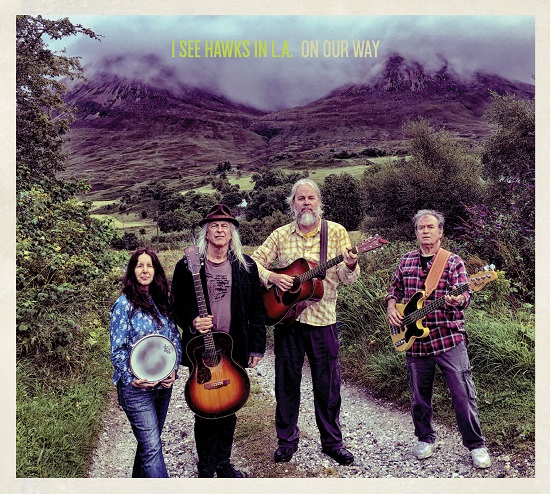

Where do I start with this one? The obvious I suppose; this is I See Hawks in LA’s lockdown album. This is the one where they discovered all of the ways of working that didn’t involve being in a room together, courtesy of Tim Berners-Lee. Rob Waller, Paul Lacques, Paul Marshall and Victoria Jacobs jumped in at the deep end and explored all the possibilities and opportunities on offer. The change in working methods and the broad church of Americana in the twenty-first century make “On Our Way” a very eclectic album indeed, incorporating elements of psychedelia, sixties pop and Southern swamp rock alongside the more usual country rock and string band arrangements. There’s a strong Byrds influence running through the whole album with twelve-string guitar featuring heavily and some gorgeous harmonies.

The album even has a pandemic song, the incredibly catchy and hook-filled “Radio Keeps Me on the Ground” which builds from an acoustic guitar intro, goes through the gears and finishes with the full band including Hammond B3. It’s an uplifting and optimistic look back at a particularly difficult year. The songs that move away from I See Hawks in LA mainstream are what gives the album its originality and depth. “Mississippi Gas Station Blues” is a grungy lo-fi, Canned Heat-inflected lope with a growling vocal, while “How You Gonna Know”, at over eight minutes long, is a constantly evolving take on a Tuareg chant with ambient sounds and general weirdness. “Know Just What to Do” is a heavily Byrds-influenced piece in triple time with chiming twelve-string and reversed guitar phrases. I’m not saying I’m endorsing this, folks, but these songs probably work better accompanied by some weed.

Victoria Jacobs gets her own song, as a writer and singer, on the album and it’s a little gem with a feel of sixties pop filtered by St Etienne. “Kensington Market” is about a visit to London in the eighties and has a dreamlike quality that works perfectly with Victoria’s vocal. There are a couple of interesting songs about historical figures; “Geronimo” tries to get inside the head of the Native American leader in later life, while “Kentucky Jesus” praises Muhammad Ali for his political and spiritual achievements rather than his boxing. Both are thought-provoking pieces.

“On Our Way” is a fascinating mix of mainstream Americana with psychedelia and a bit of grunge for good measure, topped off with Rob Waller’s mellow lead vocal and some lovely smooth harmonies. You certainly won’t be bored by this album.

“On Our Own Way” is out now on Western Seeds Record Company (WSRC – CD015).

Here’s the video for the title track:

I know there’s an awful lot of good music out there, but it’s still a shock to hear something as good as “Love” and realise that Get Well Soon and its creator Konstantin Gropper, have been around since 2008. Admittedly he’s better known in his native Germany and also better known as a film composer, but an album of this quality makes you wonder why he isn’t better known generally. This is his fourth album and you can probably guess the theme from the title but this isn’t a chocolate-box, hearts and flowers version of love, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

I know there’s an awful lot of good music out there, but it’s still a shock to hear something as good as “Love” and realise that Get Well Soon and its creator Konstantin Gropper, have been around since 2008. Admittedly he’s better known in his native Germany and also better known as a film composer, but an album of this quality makes you wonder why he isn’t better known generally. This is his fourth album and you can probably guess the theme from the title but this isn’t a chocolate-box, hearts and flowers version of love, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Gropper is highly literate and his take on the theme of love emphasises the mystery and the messiness against a constantly morphing musical background. The press release for the album helpfully supplies a list of artists that Gropper was listening to while making the album, and some of them are fairly evident in the finished product with a strong hint of early Tom Petty on “It’s Love”.

At times, the album has a symphonic feel; the opening song “It’s a Tender Maze” has an intro which is partly influenced by Eastern music and partly the sound of an orchestra tuning up before a performance, while the final song, “It’s a Fog” brings the album to a brass-led, raucous conclusion. Along the way, there are elements of disco in “Young Count Falls for Nurse”, St Etienne-flavoured pop in “It’s a Catalogue”, jangly indie in “Marienbad” and a Richard Hawley retro sixties influence in ”I’m Painting Money”. The musical quality and variety is everything you’d expect from someone who soundtracks films, and the lyrics are outstanding.

Gropper’s natural lyrical style is laced with cynicism which manifests itself here as a sense of puzzlement at the manifestations of love and the way in which it’s painted by our consumer society as he focusses on the strange and sometimes grubby aspects of the phenomenon. “It’s Love” is a song celebrating first love, but the reference to blood-stained knickers pulls it back into the physical world with a jolt. “33” is a series of little observations of the life of a person whose life has stagnated at that age and has a couple of fine lyrics which demonstrate Gropper’s wry, almost sarcastic, style: ‘your green batik doesn’t fit you no more, that’s a shame ’cause Batik’s coming back’ and ‘this year you are 33, but when you cry you still look 16’ wouldn’t sound out of place on a nineties Babybird album.

“Love” is a fascinating attempt to explore a theme that defies logical explanation. Konstantin Gropper’s answer is to admit that he doesn’t have a clue while painting perfect miniatures of the experience of love or its absence against a hugely varied set of arrangements. It works superbly.

Out now on Caroline/Universal (CAROLO10CD).

Ok, call me obsessive if you like but as well as listening to a lot of albums and going to as many gigs as I can, I also read the odd book or two about music and popular culture and many of those are worth sharing with anyone who checks out MusicRiot regularly. This list was difficult to pin down to five from the start, but it became even more difficult on Christmas Day when I was given a copy of the Donald Fagen memoir/tour diary/article compilation, “Eminent Hipsters”. So I guess that’s a pretty good place to start.

“Eminent Hipsters” – Donald Fagen

Where do I start with Donald Fagen? With Walter Becker, he was half of one of my favourite 70s bands, Steely Dan and then went on to release the classic solo album, “The Nightfly” in 1982, followed (not too closely) by “The Kamakiriad” in 1993. You’ve probably guessed by now, I’m a bit of a fan. “Eminent Hipsters” is partly an explanation, through a series of articles, of the factors which influenced the Steely Dan sound (cool jazz, cop dramas and wise-ass comedians) and the Donald Fagen solo sound (science fiction and mid-century paranoia). If you love the music, you’ll be fascinated by these observations about its roots. The second part of this slim volume is devoted to Fagen’s diary from the 2012 “Dukes of September Rhythm Revue” tour which is, by turn, snarky, moving, insightful and downright hilarious.

Where do I start with Donald Fagen? With Walter Becker, he was half of one of my favourite 70s bands, Steely Dan and then went on to release the classic solo album, “The Nightfly” in 1982, followed (not too closely) by “The Kamakiriad” in 1993. You’ve probably guessed by now, I’m a bit of a fan. “Eminent Hipsters” is partly an explanation, through a series of articles, of the factors which influenced the Steely Dan sound (cool jazz, cop dramas and wise-ass comedians) and the Donald Fagen solo sound (science fiction and mid-century paranoia). If you love the music, you’ll be fascinated by these observations about its roots. The second part of this slim volume is devoted to Fagen’s diary from the 2012 “Dukes of September Rhythm Revue” tour which is, by turn, snarky, moving, insightful and downright hilarious.

Donald Fagen writes in an instantly-identifiable style betraying a debt to Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, which sneaks in when describing Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” as getting :”out of that cab on Fifth Avenue in a black dress and pearls in the early morning, I wanted to sip her through a straw”. It’s beautifully written and you can get through it in a few hours; it takes 170 pages to deliver a message that most rock biographies take at least five times as long to get over.

“Bedsit Disco Queen: How I Grew Up and Tried to be a Pop Star” – Tracey Thorn

If Donald Fagen’s prose style is easily identifiable, then Tracey Thorn’s is even more so. I’m always impressed when musicians get this right (Peter Hook and Luke Haines also do it particularly well) and, from the first paragraph, this is pitch-perfect ‘Popstar Trace’. The book takes us from the Marine Girls beginnings through the EBTG false starts and eventual success to the beautiful Massive Attack vocals (I’m biased, but you should read about the origins of the modern classic, “Protection” here) and the worldwide Todd Terry-remixed success of “Missing”.

If Donald Fagen’s prose style is easily identifiable, then Tracey Thorn’s is even more so. I’m always impressed when musicians get this right (Peter Hook and Luke Haines also do it particularly well) and, from the first paragraph, this is pitch-perfect ‘Popstar Trace’. The book takes us from the Marine Girls beginnings through the EBTG false starts and eventual success to the beautiful Massive Attack vocals (I’m biased, but you should read about the origins of the modern classic, “Protection” here) and the worldwide Todd Terry-remixed success of “Missing”.

Tracey’s style is perfectly self-deprecatory; you never feel a hint of false modesty and the mentions of famous musicians are always very matter-of-fact, including the story about waiting to pick the kids up from school and being shouted at by George Michael from a Range Rover. This is a wonderful memoir from a genuine pop star.

“Yeah, Yeah, Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop” – Bob Stanley

It’s obvious from the outset that this is actually a companion piece to the classic 2012 St Etienne album, “Words and Music”. The album was a voyage through the history of British pop music and the book is an extended verbal remix of the ground covered by the album. What’s equally obvious is that Bob Stanley is both an enthusiast and an insider, which gives him a unique perspective on his subject. He aims to show the links between different styles using not just the music, but also sociological and technological developments. If you’re interested in the history of pop music and you’ve done a bit of research, you might disagree with some of his pronouncements, but it’s a big book and you’ll probably agree with ninety per cent of them.

It’s obvious from the outset that this is actually a companion piece to the classic 2012 St Etienne album, “Words and Music”. The album was a voyage through the history of British pop music and the book is an extended verbal remix of the ground covered by the album. What’s equally obvious is that Bob Stanley is both an enthusiast and an insider, which gives him a unique perspective on his subject. He aims to show the links between different styles using not just the music, but also sociological and technological developments. If you’re interested in the history of pop music and you’ve done a bit of research, you might disagree with some of his pronouncements, but it’s a big book and you’ll probably agree with ninety per cent of them.

The book takes the first NME chart in 1952 as its starting point (which is logical and not controversial) and the end of vinyl as a chart force in 1993 as its end point, when the first Number One singles not to have been released as a 7” single or (a few months later) on vinyl at all topped the charts (if you want to know what they are, you can buy the book ). It’s a slightly more controversial choice but still with a logical basis for someone who grew up in the age of vinyl. The book has an authority derived from Bob Stanley’s experience as a writer and member of a very successful pop group but never slips into the socio-cultural academic approach of, for example, Simon Reynolds. The theme that underpins everything else in this book is that Bob Stanley is still a fan who wants you to come round and listen to his records, and that makes this an unmissable book.

“Here Comes Everybody: The Story of the Pogues” – James Fearnley

I’ve always been a fan of the “inside story” biography, particularly those that aren’t ghost-written attempts at cultural revisionism. This memoir by James Fearnley is, at times, brutally and crushingly honest about members of The Pogues and he doesn’t spare himself either. The book begins by setting the scene with Shane MacGowan’s departure from the band in 1991 before moving back to Fearnley’s initial meeting with MacGowan at an audition for The Nips in 1980.

I’ve always been a fan of the “inside story” biography, particularly those that aren’t ghost-written attempts at cultural revisionism. This memoir by James Fearnley is, at times, brutally and crushingly honest about members of The Pogues and he doesn’t spare himself either. The book begins by setting the scene with Shane MacGowan’s departure from the band in 1991 before moving back to Fearnley’s initial meeting with MacGowan at an audition for The Nips in 1980.

The book is a (mainly) unsentimental account of the rise and fall of The Pogues from the viewpoint of someone close enough to see everything but with enough distance to retain some objectivity. From the chaotic managerless beginnings through the unpopular but successful stewardship of Frank Murray, the story is underpinned at all times by MacGowan’s unpredictability and seemingly random self-destructive urges. James Fearnley tries very hard to balance the singer’s inexcusable behaviour against the genius of the songs, but it’s up to you if you buy that line; I certainly don’t. My only criticism is that James Fearnley spends a little too much time trying to emphasise the fact that he’s a writer and occasionally introduces unnecessarily florid prose to prove it; putting that aside, it’s still a winner.

“Sounds like London: 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital” – Lloyd Bradley

Bear with me for a minute here; this will all make sense presently. Earlier this year I read “How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and the Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005” by Richard King. It’s a very good book and a must for geeks like us, but it attracted a lot of criticism because it didn’t touch on the black music scene. Richard King was even accused, pathetically, of racism in some quarters; you might even have read about it. Personally, I prefer to read authors who write about subjects they understand and that really inspire them; if Richard King didn’t have the expertise, contacts or inspiration to write about the black music scene, then Lloyd Bradley certainly did.

Bear with me for a minute here; this will all make sense presently. Earlier this year I read “How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and the Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005” by Richard King. It’s a very good book and a must for geeks like us, but it attracted a lot of criticism because it didn’t touch on the black music scene. Richard King was even accused, pathetically, of racism in some quarters; you might even have read about it. Personally, I prefer to read authors who write about subjects they understand and that really inspire them; if Richard King didn’t have the expertise, contacts or inspiration to write about the black music scene, then Lloyd Bradley certainly did.

The title is a little misleading; there’s very little about pre-1950s black music, and it also deals with regional English offshoots from the London scene but those aren’t criticisms, just observations. The reason for the comparison with Richard King’s book is that one of Lloyd Bradley’s recurring themes is that black British music has always developed and prospered healthily out of the mainstream when produced and distributed independently.

Once the book reaches the point where Lloyd Bradley can introduce interviews with the players who made black British music happen (the steel pan players, the jazzers, the sound system pioneers, the Britfunk players and the mainstream crossovers Eddy Grant, Janet Kay, Jazzie B and the rest), the narrative really takes off with stories of the sound systems and records being sold out of the back of a car and distributed around the country in the same way. Lloyd Bradley takes us through calypso, ska, reggae, lovers rock, dub, britfunk, 98 bpm, trip hop, jungle, d’n’b, UK garage, dubstep and grime along with a host of short-lived one-way streets with an unassuming and easy authority that is very seductive. If you want an introduction to black British music, this is the book for you.

OK, spoilers alert; I’ve relented. I’ll tell you that the chart-toppers Bob Stanley refers to in 1993 and 1995 respectively are Culture Beat’s “Mr Vain” and Celine Dion’s “Think Twice”, but you should still read the book. Actually you should read all of these books.

Annie is the absolute embodiment of a cult artist but also a bit of an oxymoron, she shows few signs of craving that big crossover pop smash although she appears to be the most archetypal of pop stars, but then not quite. Annie has always retained an awkwardness and appears as an introverted figure; with no massive ego and zero tabloid splashes, this is not the kind of attitude that will get you that support slot on the next Katy Perry stadium tour. This EP is not going to change that and an assumption that this was never one of Annie’s main objectives in the first place would not be naïve.

Annie is the absolute embodiment of a cult artist but also a bit of an oxymoron, she shows few signs of craving that big crossover pop smash although she appears to be the most archetypal of pop stars, but then not quite. Annie has always retained an awkwardness and appears as an introverted figure; with no massive ego and zero tabloid splashes, this is not the kind of attitude that will get you that support slot on the next Katy Perry stadium tour. This EP is not going to change that and an assumption that this was never one of Annie’s main objectives in the first place would not be naïve.

Like fellow swede Robyn before her, Annie isn’t releasing an album this time round, apparently there will be three EP’s this year, each made with a different producer/come collaborator (“Tube Stops and Lonely Hearts”, which suddenly appeared as a lone single earlier this year, was co-produced by Girls Aloud masterminds Xenomania) and the first is with anarchic pop producer and neglected genius, Richard X (the R in the title). Richard X is to Annie as Timberland once was to Missy around the turn of the last decade, the relationship goes beyond that of muse and maestro, an equal partnership that brings out the best in each artist derived from a comfort factor and desire to innovate.

These are songs about relationships with boys, or should I say men, Annie is in her thirties after all. The third track, and maybe the most pure pop moment here, is a cartoony, Casio keyboard style bleeped love letter addressed to one man in particular. “Ralph Macchio”, the actor best known for his role as the Karate Kid, is Annie’s new crush and the humour that is a trademark of Richard and Annie’s previous work is in intact and resplendent (2004’s “Me Plus One” is famously about Geri Halliwell pleading with Richard X to work with her and the cut-price diva consequences of him refusing). “Invisible”, with its Funky Drummer sample and acid squiggles, make it the most textured and interesting track the duo have come up with to date. A duet with herself, Annie’s voice is slowed down for a verse as she acts out the part of the rotten lover and then answers herself with a Boo style rap; it goes hard and is fantastic.

“Hold On” is possibly the standout song; it’s certainly the most self-assured and has some lovely, intricate musical details from Richard X (listen out for the brief, clipped steel drum sample right at the end) and a mid-tempo groove that manages to reference The Rah Band, “Break 4 Love” and St Etienne while Annie’s delicate vocals float above the whole thing beautifully. “Mixed Emotions” is sad, minor key verse major key chorus disco house which doesn’t make its presence felt as strongly as the other three tracks and “Back Together”, a co-write with Sally Shapiro obsessive (it shows) Little Boots, is straight-up pop house from 1991 although many will be too blind to see it.

Annie fans will be happy then, her and Richard X have turned their obsessive musical radar to the dance (and chart) music of the early 1990’s and particularly with “Invisible” and “Holding On”, have created tracks that would have doubtlessly appeared on The Chart Show, the frustrating but loved music video show that ran throughout the decade. These songs are neither big or stupid enough to make that kind of mainstream impact now but the world is a different place, one where Annie can get her smart and fun tunes out to her dedicated demographic and still remain pop’s best kept secret. Her choice.