“Flourish // Perish”, Braids’ 2013 ghoulish and appropriately-titled album was relentlessly electronic and micro-managed into various cerebral parts which led to several songs with a playing time of around seven minutes. Less than two years later and the Canadian female-led band, now a trio, has returned with a collection of songs that is far more human and approachable with a new, over-riding pop sensibility. Raphaelle Standell-Preston’s cut-glass voice still sounds pained and introspective in places but the accompanying sonics are tighter and more focused, brighter and with poise. They have opened up an air-tight studio and, with some trepidation, wandered outside.

“Flourish // Perish”, Braids’ 2013 ghoulish and appropriately-titled album was relentlessly electronic and micro-managed into various cerebral parts which led to several songs with a playing time of around seven minutes. Less than two years later and the Canadian female-led band, now a trio, has returned with a collection of songs that is far more human and approachable with a new, over-riding pop sensibility. Raphaelle Standell-Preston’s cut-glass voice still sounds pained and introspective in places but the accompanying sonics are tighter and more focused, brighter and with poise. They have opened up an air-tight studio and, with some trepidation, wandered outside.

“Letting Go” and “Taste” open the band’s third album and both introduce bold, simple piano chords early on that dominate the entirety of “Deep in the Iris”. The prominent acoustic instrument on the album, Standell-Preston’s vocal, is high in the mix and is also accompanied by the more expected electronic soundscapes that crash and spin elegantly around her. ‘The hardest part is letting go’, Standell-Preston repeats again and again, such is the intention to move on and begin again. On the mid-nineties electro-pop of “Taste” (listen to northern band Dubstar’s 1995 debut album ”Disgraceful”, and you can start joining the dots) the admission of ‘so I left you, but you’re actually what I like’ partly identifies the cause of this crisis.

New beginnings are referred to again on what is the most, somewhat ironically, pointedly attention-seeking song on the album, “Miniskirt”. An anthem, regardless of its intention, that reinforces the right of any woman to wear what she chooses without fear of male violence. Standell-Preston sings in a way that suggests intense personal distress and history but with the recognition that this is a depressingly age-old reaction that still lingers over women, whenever or whatever their experience. ‘It’s not like I’m feeling much different from a woman my age years ago…I’m the slut, I’m the bitch, I’m the whore, the one you hate’ over churning keyboards and beats that wind down temporarily to a quiet, piano-only sliver before Standell-Preston reasserts her self-nominated position of power and dignity.

“Sore Eyes” is both the most surprising and fully-realised track on “Deep in the Iris”. The album’s highlight, it surrenders completely to what’s been hinted at throughout and is a relentless, synth-pop stomper that demonstrates just how far the collective writing ability of the band has come. Built around a gloriously melodic, fantastically plain-speaking chorus about internet porn obsessions and the grubbiness experienced following hours of screen fixation, ‘Watched some porn and surfed until my eyes got sore again, and now I’m feeling gross and choked like everything I don’t want to be a part of. The girls with balloons and the men with batons, shoving it hard, two people being porn stars’

From “Miniskirt” to the album closer “Warm like Summer”, with its euphoric, ever-escalating middle-eight meshed between drum and bass and ever-soothing piano, the band are on a skilfully orchestrated home run. “Getting Tired” has an assured but downtrodden attitude that could be early Liz Phair with pop-art aspirations and “Bunny Rose“, with its fizzing electro glitches and naggingly catchy chorus of ‘what’s so bad with being alone? I don’t want to aimlessly throw my love around like it’s nothing’, is both rare and thoughtful in its sentiment. With “Deep in the Iris” Braids have made an album that is smart and immediate with messages and observations that are uncommon in what is essentially a brilliantly written indie-pop record; it’s one of the best around at the moment.

Californian singer-songwriter Hannah Cohen’s debut album “Child Bride” was released in 2012 and probably passed you by. “Pleasure Boy”, its follow-up, may not be the most eagerly anticipated release of 2015 but to let it slip under the radar unheard would be a crying shame. Where “Child Bride” was predominantly acoustic, withdrawn and reflective, Hannah Cohen’s follow -up has an omnipresent and altogether darker hum to it which underscores the prettier tracks creating a welcome assertiveness whilst also benefiting from a sonic diversity not heard on her debut.

Californian singer-songwriter Hannah Cohen’s debut album “Child Bride” was released in 2012 and probably passed you by. “Pleasure Boy”, its follow-up, may not be the most eagerly anticipated release of 2015 but to let it slip under the radar unheard would be a crying shame. Where “Child Bride” was predominantly acoustic, withdrawn and reflective, Hannah Cohen’s follow -up has an omnipresent and altogether darker hum to it which underscores the prettier tracks creating a welcome assertiveness whilst also benefiting from a sonic diversity not heard on her debut.

The theme of “Pleasure Boy” is romantic betrayal. Cohen has been clear that this concise, eight track album was born out of the debris of a bad breakup and the boy of the title, all fun but commitment-phobic, seemed to cause her considerable but not irreparable damage. Produced again by Thomas Bartlett aka Doveman, a musician in his own right with collaborations with The National, Antony and the Johnsons and Martha Wainwright, the introduction of beats and a recurring synth-pop feel are satisfyingly immediate under his supervision. Classical arrangements, jazz and trip-hop also slip in and out of earshot and are anchored by Cohen’s skilled, subtle song writing.

“I’ll Fake It” has a rogue synth line that will snake into your left ear; “Pleasure Boy” is an album that benefits from headphone use, dominant bass and a thumping, knocking percussion. ‘I know a good girl when I see one, and this one’s out for blood’ insists the pop chorus which is the album’s most blatant attempt at a commercial sound. “Watching You Fall” will inevitably draw Lana Del Rey comparisons: ‘I’m no kid, I’ll take you apart’ where Cohen’s voice is still disconcertingly coy and seductive and swaggering atop the rolling beats and Angelo Badalamenti style strings. “Take the Rest”, by comparison, with its wheezing synth hook, diverts into a warm and layered jazz-pop chorus.

“Claremont Song” is deliciously lush and heartbreaking with woodwind instrumentation and every crucifying word audible: ‘sing me the most beautiful thing that you could ever sing, now hurt me more until nothing else hurts then walk away from me’. The flip side to this self-punishing ritual, and they effectively lie back-to-back in the album’s track listing, is the appropriately titled “Queen of Ice”. Cohen suspended by demonic and hushed noises-off, and a staccato sax riff adding further tension; this jazzy noir is indeed possessed, rebuilding strength maybe, but at what cost? “Baby” ends the album with an acoustic piano and guitar in a throwback to the more singular sound of her debut.

Structured more like an extended, EP as opposed to an album with its total running time at just over thirty minutes, “Pleasure Boy” could not afford to carry dead wood and Hannah Cohen has seen to it that any slack has been trimmed right back. Beautifully crafted, devastating on occasion but relatable and delivered with a supreme lightness of touch. Do yourself a favour and make certain you seek this one out.

Florence + The Machine is a relatively rare and interesting type of multi-million selling global superstar to be found in this or even the past decade. She is more suited to the mid-eighties/nineties stretch of pop stars that included Kate Bush, Prince and Bjork – artists that used idiosyncratic and sometimes iconoclastic imagery that was key to their success but didn’t define it and whose music was frequently strange and brilliant but sold by the shed load. Where Florence Welch differs from her idols though is that her musical choices so far have found the singer already approaching what could be regarded as caricature of herself. Her debut album “Lungs” was a rag-tag but solid collection of goth-pop which established her eclectic eccentricity and 2011’s highly polished “Ceremonials” had some fantastic songs which were often marooned in a samey, shouty and exhaustingly one-note soundscape. “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful” sees Florence set out to actively change this, to breath nuance and restraint and personal experiences into an album’s worth of songs.

Florence + The Machine is a relatively rare and interesting type of multi-million selling global superstar to be found in this or even the past decade. She is more suited to the mid-eighties/nineties stretch of pop stars that included Kate Bush, Prince and Bjork – artists that used idiosyncratic and sometimes iconoclastic imagery that was key to their success but didn’t define it and whose music was frequently strange and brilliant but sold by the shed load. Where Florence Welch differs from her idols though is that her musical choices so far have found the singer already approaching what could be regarded as caricature of herself. Her debut album “Lungs” was a rag-tag but solid collection of goth-pop which established her eclectic eccentricity and 2011’s highly polished “Ceremonials” had some fantastic songs which were often marooned in a samey, shouty and exhaustingly one-note soundscape. “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful” sees Florence set out to actively change this, to breath nuance and restraint and personal experiences into an album’s worth of songs.

Markus Dravs has taken over almost all production duties from Paul Epworth (who still co-produces one track here) and has laid down the law, it seems, telling Welsh that certain well-worn subjects are off-limits, such as water metaphors (a few still slip through the net, excuse the pun) and an early song called “Which Witch” bought to him by Welch was rejected because of song title only (and that too still appears, but as a bonus track only). He wanted to put her voice up front and to be more exposed and vulnerable, less multi-tracked, and for the music to also have space to breathe. Will Gregory, the introvert half of Goldfrapp, was bought on board as Welch wanted lots of brass and she’s certainly got her wish. It seems that there was some compromise on both sides, as this is a different Florence album in part, but it is not to be considered as any real, radical departure in sound. With the strength of songwriting on display here and a successful transition to more interesting and diverse soundscapes this is not important, it’s the most balanced and cohesive album that Welch has made thus far.

The first song to be heard from “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful” was the striking “What Kind of Man”. With Welch’s voice manipulated to echo that of Karin Andersson from The Knife, she sounds genderless and possessed and it’s something of a shame that guitars and drums crash in all too soon. The mania and panic associated with Welch and evidenced here again is offset beautifully by a return to the coolness of this initial refrain though and “Ship to Wreck”, with its soaring near gospel middle-eight, continues with the indie rock motifs . The title track’s opening line ‘between a crucifix and the Hollywood sign’ is not the only thing that sounds like you might hope a Madonna track would in 2015; it has a spaciness and warmth that is designed to be heart- swelling and it is. The long instrumental play-out is the most optimistic that a Florence track has ever sounded, assertive trumpets and forthright strings herald a new dawn with all of its possibilities. Sounds cheesy perhaps but it’s sincere and as gorgeous as hell.

“Various Storms & Saints” and “Long & Lost” continue with an acoustic, bare bones but lush instrumentation and “Caught” is a mid-tempo r’n’b song with an unexpected country sway and is swoonsomely heartbroken. Over a plaintive organ and understated orchestration it is “St Jude” which cements absolute melodic perfection with Welch’s forever fallen angel, compulsively drawn to chaos. “Delilah” and “Third Eye” will delight the Florence diehards with both tracks pulling across the established, bombastic and commercial sound from her previous two albums and turning the dial up even further to not-quite ludicrous settings. Album closer “Mother” incorporates all of these ingredients but stirs them about with a 1970’s blues-rocker shtick that creates something altogether more strange and the final, thrashing fifty seconds genuinely excite. Florence + The Machine may never be able to do subtle but with “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful”, Welch has made considerable progress with making music that is more complex, satisfying and timeless sounding than before, never alienating her current fan base and undoubtedly attracting many more new ones in the process.

‘How will I sing us out of this sorrow?’

‘How will I sing us out of this sorrow?’

Following eight albums that have all been conceptual to varying degrees and have covered such themes as introversion, extraversion, the voice as a multi-instrument and musical nature via apps it is both shocking and affecting to experience Bjork’s latest subject, herself and her family. Bjork, artist Matthew Barney and their children have demonstrated ably that is possible to retain privacy no matter however big your star may be and however hard a brutal media tries to prick it. With “Vulnicura” then a massive rupture has occurred to the point where Bjork specifies which songs on the album relate to which periods in the relationship when the rot began to set in for her and Barney, who are now most definitely separated following over a decade together as a kind of exotic, unattainable art couple. The fact that this album originally appeared two months earlier than its intended release date, because of a full online leak, and with no promotional material only added to the voyeuristic tingle and brutality of the unexpected openness that Bjork allows us.

There is no return to left-field pop or immediate accessibility on “Vulnicura”. The majority of the nine tracks are well over six minutes long; “Black Lake” is just over ten, and there are surprising nods to her late nineties material throughout. There are some gorgeous melodies here but the album is structured, and to a large extent sounds exactly like, a classical piece, which is primarily due to the return of gigantic, stirring and occasionally violent string parts – only the shortest track does not feature an orchestra. Opening track for example, “Stonemilker”, set ‘nine months before’, is lush, stately and warmly reassuring and suggests little unrest. But the first audible line ‘moments of clarity are so rare, I’d better document this’ indicate frustration and the interruption of stability.

“Lion Song” opens with the kind of stacked-up and distorted accapellas first heard on “Medulla” but this is not an indication of what follows. ‘Maybe he will come out of this (loving me), maybe he won’t, somehow I’m not too bothered either way’ is a typically poetic, plain-speaking Bjork lyric and forms the sweeping and woozy, eastern-influenced chorus; the friendliest on the album. This is tied together by verses that are led by the string arrangements and which dip and dart broadly in a style most resembling a cautionary show tune. “History of Touches” accounts the last time a couple sleep together following years of unity and togetherness. It’s probably the saddest song here and is beat-less with ethereal but zig-zagging synths supporting an accepting and almost disconcertingly confident vocal.

“Black Lake” is the eye of the storm, ‘my shield is gone, my protection is taken’. Lines are sung in a plaintive, near-defeated way before string notes are drawn out for up to almost 30 seconds to seemingly allow Bjork to recompose and continue. Straightforward songwriting and exquisite orchestration dominate and at one point beats threaten to take the mood elsewhere but such interruptions are premature and silenced by violins. Devastating but restrained, it is Bjork playing to all her strengths.

The second half of the album, songs that deal predominantly with the post-relationship period, has several tortured, schizophrenic movements that are contained within the songs themselves. “Family” and “Notget” are “Vulnicura”’s most difficult tracks and also provide some of its most artful and sonically visceral moments. Fully immersed in rage, bewilderment and the almost liberating feeling of letting go of something that has ended, however paining. “Family” opens with the astonishing line ‘is there a place that I can show my respects for the death of my family?’ and is musically ominous, becoming increasingly terrifying. Both these songs are co-written and produced by Arca and are where his presence is most felt, those however expecting “Vulnicura” to sound like an Arca record with Bjork vocals will be disappointed. The creaking and constantly erupting beats and soundscapes, overall, still sound more or less as they always have done – like a Bjork record. The final third of the album is about recovery, friendship and moving forward and final track “Quicksand”, all luminous electronics, staccato strings and drum and bass, speaks about the future of women and the need to accept adversity as well as joy.

“Volta” and “Biophilia”, albums that immediately proceeded this, were often deliriously chaotic, cryptic and for the most part interesting, but lacked the essential emotional core that has grounded all of Bjork’s work; on “Vulnicura”, we are again back on steady ground. With her career retrospective at the MOMA, spanning the last twenty years of her work, it is both a relief and a genuine thrill to have one of pop’s most important, explosive and influential stars making music that again matches, and in places surpasses, her best. Bjork has, as she has always done, followed her heart in order to heal her heart and never has this sounded as critical as on “Vulnicura”. Singing her way out of sorrow is instinctual and much more than a career move, it has helped save her and for that we should be grateful.

Hyperbole surrounding the importance of 18+’s identity, ironically a key selling point for this celebrity-averse duo’s brand, has run its course. In some ways it was only a matter time. Interviews are given, live performances attended and there, smack bang in the centre of “Trust”’s cover art, the couple finally appear, photographed together, in brutal and beautiful profile. If American musicians Samia Mirza and Justin Swinburne (previously referred to as just Boy and Sis) had wanted to remain anonymous for longer, then they could have done but the decision to be unmasked appears to be of their own making. After months of slightly sinister CGI videos, which could have gone much further than they did, we now can reimagine these songs with portraits of the actual performers themselves and not the carefully stage-managed visuals as dictated by the duo. Whether or not this has been a mistake and somehow weakened the appeal of 18+ isn’t important. What we have been ultimately left with is the music unaccompanied by any surplus hype. “Trust” is not a multi-media release and thankfully there is just enough sonic expertise and craft to allow it to stand unassisted.

Hyperbole surrounding the importance of 18+’s identity, ironically a key selling point for this celebrity-averse duo’s brand, has run its course. In some ways it was only a matter time. Interviews are given, live performances attended and there, smack bang in the centre of “Trust”’s cover art, the couple finally appear, photographed together, in brutal and beautiful profile. If American musicians Samia Mirza and Justin Swinburne (previously referred to as just Boy and Sis) had wanted to remain anonymous for longer, then they could have done but the decision to be unmasked appears to be of their own making. After months of slightly sinister CGI videos, which could have gone much further than they did, we now can reimagine these songs with portraits of the actual performers themselves and not the carefully stage-managed visuals as dictated by the duo. Whether or not this has been a mistake and somehow weakened the appeal of 18+ isn’t important. What we have been ultimately left with is the music unaccompanied by any surplus hype. “Trust” is not a multi-media release and thankfully there is just enough sonic expertise and craft to allow it to stand unassisted.

‘Lap, fuck, hair, fingers, taste, down, spit, clit, dry’; words that you’ll hear more than once over “Trust”’s playing time confirming a persistent, glitchy nihilistic tone throughout. 18+ really enjoy singing about sex but whether they actually enjoy it is unclear. All of the tracks on “Trust” have been selected from their previous three mixtapes and 18+ have been making music together for several years now, so unless you’re completely unfamiliar with their material there are no surprises here. “Crow”, one of the duo’s biggest songs to date, still stands out as the most accessible and immediate track due to repetitive tropes including finger- clicks, booming bass and, appropriately enough, a crow’s caw. It is also one of the album’s most melodic moments, something that 18+ need to focus on, and features a typically slippery but assertive vocal from Mirza who welcomingly refuses the victim role throughout.

“Forgiven” owes a debt to Kelis’ Milkshake with its skeletal nursery rhyme feel and highly sexualised motifs and “Almost Leaving” is essentially indie shoe-gaze and is quietly lovely. “OIXU”, another highlight, sounds like The xx and Sugababes (first generation) trading verses and chorus respectively. It’s not important that 18+ don’t offer anything original here, it’s the quality that counts after all, but aside from a dominant trap influence it is again nineties trip-hop which most comes to mind. Listen for example to Tricky and Martina Topley- Bird’s “Makes me Wanna Die” and compare its ambitions musically to at least half the tracks here and on many levels it’s difficult to feel that almost twenty years has passed since the former’s release. Of course a lot of trip-hop was interested in exploring emotional connections as well as sexual, much like FKA Twigs today, and this is where the likes of 18+ differ. The faceless and tireless disconnect and reinvention options that the internet offers informs everything about Mirza and Swinburne’s approach including the finished work itself.

18+ had the opportunity on “Trust” to expand and refine their ideas based on what’s come before and maybe that’s the biggest disappointment, their failure to develop or to fill in some of the missing details. Songs where Swinburne dominates, “Club God” for example, don’t work as well, as he just doesn’t have either the presence and authenticity of his partner in crime. Self-contained, claustrophobic and still somewhat shallow, the pair has really worked hard in creating an enveloping, somewhat sleazy mood but occasionally this is at the cost of the required depth or imagination to prevent it becoming, over the course of an entire album, dull and repetitive. There are some sparkling ideas here though and it can be only hoped, following the ultimate reveal of Samia Mirza and Justin Swinburne as 18+, that they can further craft their vision and soundscapes into something even more compelling and consistently captivating.

Jazmine Sullivan’s third album comes after a five-year break and follows a period of personal turmoil and subsequent self-discovery for the big-lunged Philly r’n’b singer. “Reality Show” may suggest something both toe-curlingly revealing and tackily brash but Sullivan’s elegant but charged timbre and monologues couldn’t be further from this. There is also some fun to be had to here though, more than might possibly be expected given the reason for Sullivan’s break, and a distinct cohesiveness throughout which given the scattershot of styles chosen is quite an accomplishment. And this is an album that Sullivan has invested heavily in; co-producing, writing and selecting material that reflect her choices as an artist returning to the game where even a year out can result in negative speculation.

Jazmine Sullivan’s third album comes after a five-year break and follows a period of personal turmoil and subsequent self-discovery for the big-lunged Philly r’n’b singer. “Reality Show” may suggest something both toe-curlingly revealing and tackily brash but Sullivan’s elegant but charged timbre and monologues couldn’t be further from this. There is also some fun to be had to here though, more than might possibly be expected given the reason for Sullivan’s break, and a distinct cohesiveness throughout which given the scattershot of styles chosen is quite an accomplishment. And this is an album that Sullivan has invested heavily in; co-producing, writing and selecting material that reflect her choices as an artist returning to the game where even a year out can result in negative speculation.

“Dumb” is the smart, albeit misleading, opener and first single of “Reality Show”. Smart because it immediately reconnects to the Sullivan sound of 2008’s, Grammy-nominated “Bust Your Windows”; it’s operatic, audacious and built around that mesmerising pure soul voice. It’s also a very good song and sounds very much of its time. Misleading in the sense that it doesn’t reflect the rest of the album, at least sonically. It makes its point, sets the scene before retreating to allow for more subtle and unexpected sounds.

“Mascara” is one of a triptych of songs that have a sixties girl group sentiment and sound. The most contemporary sounding of the three, “Mascara” is a lyrically ambiguous song that at first seems to be a ‘make the best of yourself’ ode to faking it when you’re actually breaking down a little inside. A closer listen confirms that Sullivan has adopted the persona of a defensive, insecure woman who hates other women and would do anything to keep hold of her partner, whatever the compromise in her dignity. It’s smart and buoyant and proves Sullivan can trip up a complacent listener. “Stupid Girl” is a juddering, snare rolling retro track that brings to mind Mark Ronson’s more playful Amy Winehouse productions and the relentless Motown thwack of “If You Dare” sends Sullivan soaring above a positive-thinking anthem that has genuine energy and power.

“Silver Lining” is a glorious, airy late seventies r’n’b style mid-tempo track where vocally Sullivan conveys desperation, optimism and indifference over three minutes so effortlessly that it’s hard to avoid comparisons to the truly great soul vocalists from the past four decades. “#HoodLove” also has moments where it’s possible to believe that Aretha Franklin herself has made a hard – nosed but ultimately romantically blind-sighted (‘he aint always right, but he’s just right for me’) ghetto tribute. “Masterpiece (Mona Lisa)”, an ode to self-acceptance, takes its sonic cues from eighties Quincy Jones balladry and the electro-disco of the brilliant and inspired “Stanley”, an obvious highlight here, features a surprising sample of Annie’s Scandi-pop hit “Greatest Hit” of all things. A put upon girlfriend, Sullivan urges her feckless Stanley to wake up, smell the roses and ‘take a bitch to dinner!’

At a time when female r’n’b is confidently stepping out of the rut it tended to find itself in during the EDM days of the early 2010s and could indeed be heading for another renaissance period, Jazmine Sullivan has made an album which sounds reassuringly timeless in spite of its various retro influences. Although there are still many detailed and modern sonic flourishes here, the spotlight, as might be expected, falls on Sullivan’s exceptional vocal abilities and for the best part, the songs are more than good enough to support her talent. There may be little here that is ground-breaking but Reality Show has little use for trick photography or fashionable gimmicks. Jazmine Sullivan is a shocking scene stealer and is wonderfully showcased here on what may well be her most thought out and intriguing album.

At the very least, the dramatic and unexpected release of Azealia Banks’ debut album is a relief. Her one bona fide hit, the filthy and fantastic “212”, was released in 2011 and talk of her first album, mainly by Banks herself, has been on, off and on again pretty much consistently since then. Some three years later and Beyonced onto iTunes at 7.00pm on a cold Thursday in early November “Broke with Expensive Taste” finally saw the light of day. We can all now move on; Banks, the naysayers, the many she has horrified with brattish abuse via her volatile twitter account – let’s go and fix our glare on the new kid. Maybe the surprise then is that there is a lot more to Azealia Banks than being a big dirty mouthed one- hit wonder. The breadth and rush of the consistently surprising, eccentric but accessible tracks here is absolute proof that she knew what she was doing all along. One of the most interesting and revealing aspects of Azealia Banks first full length release proper is all of the things that it is not. There is no EDM, and although this is most definitely a dance record, no dubstep, no grand-standing features and no sign of the kind of producers that eclipse the artist themselves and are usually called in for last minute emergencies. In fact the one track that was produced by and featured the ubiquitous Pharrell Williams (the lacklustre and generic “ATM Jam”) has wisely been left off. The Williams collaboration was forced upon Banks by her then record company (she has since left Interscope, to call it a rocky relationship would appear an understatement) to bag an easy hit, as is often the case, and by all accounts represents the reasons why “Broke with Expensive Taste” has suffered such a long and bumpy ride to release. Banks is not an artist who is willing to compromise or curtail her artistic impulses and this is made abundantly clear here. Album opener “Idle Delilah” has clattering pots and pans percussion, a fuzz-box island guitar riff and a chorus, if it can indeed be called that, that consists only of a chopped- to- utter -smithereens Brandy sample from her hit “I Wanna Be Down” which is rendered utterly unrecognisable here. This is to support Banks warbling but radiant rap and vocal lines laid out over a building house beat. “Desperado” and “Gimme a Chance” go down different roads entirely; the former has Banks speeding sulkily over an old and moody MJ Cole 2-step track, “Bandelero Desperado”, with muted trumpet and an unmistakeable British identity whilst “Gimme A Chance” references early hip-hop scratching and a Ze Records “Off the Coast of Me” dead – eyed sung chorus. This all comes before the second half of the track which explodes into Latin American horns with Banks both singing and rapping in Spanish. “JFK” is a snooker balls-cracking house track with vocal inflections mimicking an almost operatic narrative of the vogue balls and creative rivalry and “Wallace” has dark cavernous drums, a blink and you’ll miss it Missy Elliott reference, and might be about a dog. At this point it is hard to accept that the album has not even reached its half-way point, such is the diversity and ambition that is alluded to. The album’s middle section is its most conventional and traditionally urban, all of the tracks are rapped. “Ice Princess” in particular, which is a variation on Morgan Page’s “In The Air” hit, proves that Banks can more than hold her own in commercial rap; her rhymes are effortless and engaging, often surreal, with a flow that is sharp but soothing. “Soda” is a popping, taut house track that sounds like little else coming out of the urban genre or any other stable at the moment and is completely sung in Banks highly distinctive swooping, and occasionally flat, contralto. It introduces the last act of the album and at this point some of the admittedly unexpected flow of the first half does suffer, due mainly to “Nude Beach a Go-Go”. Produced by Ariel Pink with an intense love or loathe quality, it sounds like a Beach Boys carol about the joys of nude beaches (‘Do you jingle when you dingle-dangle? Everybody does the bingle-bangle’) as imagined by the B 52s who already have a song called ‘Theme for A Nude Beach’. It is quite a lot to take in and is probably brilliant but is jarringly sandwiched between the album’s deepest house tracks, the alluring triptych of “Luxury”, “Miss Camaraderie” and “Miss Amor”. The decision to include older tracks here, including ones already featured in Banks 2012 “Fantasia” mixtape (and yes, “212” is also here), is the only misstep that hinders the irresistible freshness “Broke With Expensive Taste”. Not only are they the weaker tracks in the majority but they overload the track listing to sixteen and subsequently dilute the potential power of the lesser-heard and superior material. The real surprise here though is that Azealia Banks could not get this album released in the first place; this is the stuff that classic debut albums are made and is massive indictment of the state of the music industry in 2014. An unreserved success still, with “Broke with Expensive Taste”, Azealia Banks has ably demonstrated that the fight was most definitely worth it and has emerged from the other side as an important, original and necessary artist.

At the very least, the dramatic and unexpected release of Azealia Banks’ debut album is a relief. Her one bona fide hit, the filthy and fantastic “212”, was released in 2011 and talk of her first album, mainly by Banks herself, has been on, off and on again pretty much consistently since then. Some three years later and Beyonced onto iTunes at 7.00pm on a cold Thursday in early November “Broke with Expensive Taste” finally saw the light of day. We can all now move on; Banks, the naysayers, the many she has horrified with brattish abuse via her volatile twitter account – let’s go and fix our glare on the new kid. Maybe the surprise then is that there is a lot more to Azealia Banks than being a big dirty mouthed one- hit wonder. The breadth and rush of the consistently surprising, eccentric but accessible tracks here is absolute proof that she knew what she was doing all along. One of the most interesting and revealing aspects of Azealia Banks first full length release proper is all of the things that it is not. There is no EDM, and although this is most definitely a dance record, no dubstep, no grand-standing features and no sign of the kind of producers that eclipse the artist themselves and are usually called in for last minute emergencies. In fact the one track that was produced by and featured the ubiquitous Pharrell Williams (the lacklustre and generic “ATM Jam”) has wisely been left off. The Williams collaboration was forced upon Banks by her then record company (she has since left Interscope, to call it a rocky relationship would appear an understatement) to bag an easy hit, as is often the case, and by all accounts represents the reasons why “Broke with Expensive Taste” has suffered such a long and bumpy ride to release. Banks is not an artist who is willing to compromise or curtail her artistic impulses and this is made abundantly clear here. Album opener “Idle Delilah” has clattering pots and pans percussion, a fuzz-box island guitar riff and a chorus, if it can indeed be called that, that consists only of a chopped- to- utter -smithereens Brandy sample from her hit “I Wanna Be Down” which is rendered utterly unrecognisable here. This is to support Banks warbling but radiant rap and vocal lines laid out over a building house beat. “Desperado” and “Gimme a Chance” go down different roads entirely; the former has Banks speeding sulkily over an old and moody MJ Cole 2-step track, “Bandelero Desperado”, with muted trumpet and an unmistakeable British identity whilst “Gimme A Chance” references early hip-hop scratching and a Ze Records “Off the Coast of Me” dead – eyed sung chorus. This all comes before the second half of the track which explodes into Latin American horns with Banks both singing and rapping in Spanish. “JFK” is a snooker balls-cracking house track with vocal inflections mimicking an almost operatic narrative of the vogue balls and creative rivalry and “Wallace” has dark cavernous drums, a blink and you’ll miss it Missy Elliott reference, and might be about a dog. At this point it is hard to accept that the album has not even reached its half-way point, such is the diversity and ambition that is alluded to. The album’s middle section is its most conventional and traditionally urban, all of the tracks are rapped. “Ice Princess” in particular, which is a variation on Morgan Page’s “In The Air” hit, proves that Banks can more than hold her own in commercial rap; her rhymes are effortless and engaging, often surreal, with a flow that is sharp but soothing. “Soda” is a popping, taut house track that sounds like little else coming out of the urban genre or any other stable at the moment and is completely sung in Banks highly distinctive swooping, and occasionally flat, contralto. It introduces the last act of the album and at this point some of the admittedly unexpected flow of the first half does suffer, due mainly to “Nude Beach a Go-Go”. Produced by Ariel Pink with an intense love or loathe quality, it sounds like a Beach Boys carol about the joys of nude beaches (‘Do you jingle when you dingle-dangle? Everybody does the bingle-bangle’) as imagined by the B 52s who already have a song called ‘Theme for A Nude Beach’. It is quite a lot to take in and is probably brilliant but is jarringly sandwiched between the album’s deepest house tracks, the alluring triptych of “Luxury”, “Miss Camaraderie” and “Miss Amor”. The decision to include older tracks here, including ones already featured in Banks 2012 “Fantasia” mixtape (and yes, “212” is also here), is the only misstep that hinders the irresistible freshness “Broke With Expensive Taste”. Not only are they the weaker tracks in the majority but they overload the track listing to sixteen and subsequently dilute the potential power of the lesser-heard and superior material. The real surprise here though is that Azealia Banks could not get this album released in the first place; this is the stuff that classic debut albums are made and is massive indictment of the state of the music industry in 2014. An unreserved success still, with “Broke with Expensive Taste”, Azealia Banks has ably demonstrated that the fight was most definitely worth it and has emerged from the other side as an important, original and necessary artist.

It goes without saying that each generation gets the pop stars it deserves. Of the ones remaining and still performing, Madonna, Boy George and Prince belong to what could be called my era, not too shoddy. This current batch of kids will eventually become nostalgic about Beyonce, Adele and, I’m sorry, One Direction. In the last five years Taylor Swift has been riding their coat-tails with her persistent country -pop and, for better or worse, she may turn out to be the biggest pop star of them all, certainly of 2014. “1989”, Swift’s fifth album, is not only the year of her birth but also refers to the eclectic and idiosyncratic musical chart toppers of that same year, part of my era, and which allegedly inspired her to finally, and somewhat predictably, make the full transition to that of a pop star.

It goes without saying that each generation gets the pop stars it deserves. Of the ones remaining and still performing, Madonna, Boy George and Prince belong to what could be called my era, not too shoddy. This current batch of kids will eventually become nostalgic about Beyonce, Adele and, I’m sorry, One Direction. In the last five years Taylor Swift has been riding their coat-tails with her persistent country -pop and, for better or worse, she may turn out to be the biggest pop star of them all, certainly of 2014. “1989”, Swift’s fifth album, is not only the year of her birth but also refers to the eclectic and idiosyncratic musical chart toppers of that same year, part of my era, and which allegedly inspired her to finally, and somewhat predictably, make the full transition to that of a pop star.

Max Martin has produced and written for the cream of Billboard magazine’s sweethearts over the past decade and a half and Swift called on him to help with a clutch of songs for her last album, the gazillion-selling ‘Red’. Those tracks were the ones that provided the album with a contemporary pop sheen, dubstep and more heavily electronic soundscapes featured, and some of its biggest hits. Martin returns here with the weightier task of almost full production responsibilities of “1989” and co-writes with Swift herself. He does a consistently robust and appropriately timeless job here and, between the two of them, the songs are frequently sharp, smart and exhilarating and avoid any of the obvious potential pitfalls; no features, no EDM and no Dr Luke.

The best moments here, and there are many to choose from, are the more thundering and urgent guitar, drums and synth tracks that call to mind pop acts such Go West, Simple Minds and Kelly Clarkson. “Out of the Woods” is not only the biggest success here, Swift’s sneer is surprisingly apparent and the gulping repetitive chorus is perfect, but almost the most lyrically competent and stylish. “All You Had to Do Was Stay” with its cheeky vocal nod to the Eurythmics, “I Wish You Would” and “Bad Blood” all provide rollicking middle-eights, tight arrangements and artful choruses that all make the intended impact. “Style” is an elegant mid-tempo electro soon-to-be chart topper which offers up the hookiest chorus – and that’s saying something here – and “Wildest Dreams” is as close as Swift gets to a mood piece although it owes quite a debt to the omnipresent Lana Del Rey sound.

The rest of “1989” is serviceable enough but lacks the passion of the better tracks and struggles to live up to the album’s conceit. “Welcome to New York” is not only one of the very worst, most insipid songs written about the city – and also a rare moment when the album also slips into musical parody of the period it’s influenced by – but it is almost a genuine reflection of it as seen through the Swift’s eyes as a recent, over-excited new comer. It also highlights just how bland and naïve lyrically many of these songs are; Starbucks lovers, it’s all good, haters and players and “How You Get the Girl”, even if used with irony, make the album sound like a massive corporate tie-in with a particular brand of young girls who can afford to live in a big city. Since the album’s release Swift has indeed, and not without controversy, been appointed as an official ambassador of New York; it wasn’t like this with Debbie Harry.

If Swift were to be a representation of the very best that pop could offer in 2014 then “1989” would confirm that pin sharp songwriting and hooks were still in abundance and lush, enveloping production was of a consistently high standard. But within the genre that is only one part of many essential components. Her previous albums have been built on an authentic and believable persona where it was possible to identify the style of the song – the actual sound of it – with the singer; here she sounds technically proficient but for the main part generic. The major players of the last thirty years right up to and including Beyonce and Adele have all developed a sound that is quintessentially theirs but Swift has failed to do that here; there is nothing exceptional or original about the way “1989” sounds. It is unlikely that her next few records will see a return to country music so maybe they will continue to build on Taylor Swift’s respect for pop and see her as confident enough to be as unpredictable and individual as her idols; or maybe she is readjusting the standard.

The objective Zola Jesus set herself for her fourth album was to face her own fears about how her love for pop music would eventually have to inform her work and what that might sound like. It is significant maybe that the oldest song here and the one that finally forced Jesus into the glare of potential mainstream and started the ball rolling, “Dangerous Days”, is also the purest pop song on “Taiga”. It has a brightness that contradicts its title, a brilliant pre chorus, an actual chorus which is only slightly less captivating and a sonic energy that’s slick and addictive and brings to mind the slightly more intricate and risky songs from Madonna’s mighty “Ray of Light” album.

The objective Zola Jesus set herself for her fourth album was to face her own fears about how her love for pop music would eventually have to inform her work and what that might sound like. It is significant maybe that the oldest song here and the one that finally forced Jesus into the glare of potential mainstream and started the ball rolling, “Dangerous Days”, is also the purest pop song on “Taiga”. It has a brightness that contradicts its title, a brilliant pre chorus, an actual chorus which is only slightly less captivating and a sonic energy that’s slick and addictive and brings to mind the slightly more intricate and risky songs from Madonna’s mighty “Ray of Light” album.

The remainder of Taiga is not really a pop record although it frequently aspires to be one. Soundscapes are stripped almost entirely of any of the glitch that featured on 2011’s “Conatus” or the muddy density on her brilliant breakthrough album “Stridulum II” and replaced by something that is undeniably big and rich but simpler and more concentrated than before. A lot of the songs have beautiful, powerful intermissions; it’s just that too frequently the melodies are lacking the strength to push these tracks to required level, the one which you presume she had in her sights. Dean Hurley co-produces with Jesus and is an odd choice given his primary job as David Lynch’s new sound man, responsible for producing both of Lynch’s inconsistent and naive solo albums, and hardly a name synonymous with making music that can be sung along to. There are references here to the Ryan Tedder meets Sia school of Beyoncé power pop on the crashing but dull “Lawless” and the Rihanna-phrased “Long Way Down” but neither songs would pass the pop queen’s test of a tune that hijacks relentlessly.

The more successful tracks, and “Taiga’” is the definition of a front-loaded album, happen in the first half. “Dust” has a woozy, avant r’n’b doo-wop swing which is hypnotising and commercially-minded and “Go (Blank Sea)” like Petula Clark, and hundreds after her, successfully sees Jesus pining for the eternal pop never-never land of “Downtown”. “Hunger” has a thrusting and bewildering attack of beats, brass and synths – at one point it’s hard to distinguish between the two- and a glacial, persistent string part and is exhilarating and sharply euphoric. “Ego” is a suspended hymn of considerable power where all of “Taiga”’s elements fall into place; a lucid and possessed vocal interrupted by sheets of brass that morph effortlessly into aching strings. The ongoing presence of strings and brass in particular bear out the theory that “Taiga” is more of a continuation of the stripped down “Versions” of last year then something you might hear in a bar. From here on in and midway through “Taiga”’s playing time the focus is lost, however, and gives way to repetition and mediocre tunes. “Hollow”, for example, attempts to salvage some drama and presence but is an oddly similar reimagining of the far superior “Hunger”.

Since the release of “Taiga”, Jesus has been remixed by the likes of The Juan Maclean and Diplo, a still relatively underground sophisticated pop-dance act, and the man rumoured to be producing the next Madonna album. Both artists have done commendable jobs in highlighting the hooks in what were admittedly already two of the album’s stronger songs (“Dangerous Days” and “Go”). Where their real strength lies, though, is in taking Jesus’ music to a demographic previously unaware of her and potentially initiating an interest to investigate further. This is where Jesus and “Taiga” stumble as the initial promise of something different and more accessible is never really delivered so new fans are unlikely to convert and current ones will be dissatisfied at the loss of the incredible depth and half-shaded mystery that permeated her earlier work. A good album still with some great songs but “Taiga” doesn’t quite provide the soundtrack that Zola Jesus commands and deserves, whether she continues to chase her big pop arrival remains to be seen but you feel that this isn’t it.

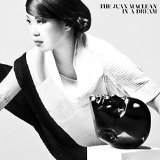

‘Flights, in the night’ sings Nancy Whang conspiratorially during a quiet portal in the impressively detailed “A Place Called Space” that opens The Juan Maclean’s third album proper. Nothing sums up Whang and Maclean’s manifesto quite as perfectly as that line. Alluding to a retro glamour which no longer exists and a promise of a decadent and clandestine other world where the only light is artificial and strobing. This line, better still if it were morphed into a song title, could have been uttered on any number of Donna Summer’s tracks which featured on her most essential, electronic and nocturnal albums made between 1977- 1979 and produced by Giorgio Moroder. As if to hammer this point home Whang has simultaneously released an EP under her own name which is a collection of Casablanca records cover versions, it includes a faithful interpretation of Summer’s slippery and melancholic “Working the Midnight Shift”. “In A Dream” is a record that may wear its influences heavily on its sleeve but the cluster of magnificent songs and the vocal dynamics honed between the two prevents it from falling into a potentially deep hole of nostalgia and tribute.

‘Flights, in the night’ sings Nancy Whang conspiratorially during a quiet portal in the impressively detailed “A Place Called Space” that opens The Juan Maclean’s third album proper. Nothing sums up Whang and Maclean’s manifesto quite as perfectly as that line. Alluding to a retro glamour which no longer exists and a promise of a decadent and clandestine other world where the only light is artificial and strobing. This line, better still if it were morphed into a song title, could have been uttered on any number of Donna Summer’s tracks which featured on her most essential, electronic and nocturnal albums made between 1977- 1979 and produced by Giorgio Moroder. As if to hammer this point home Whang has simultaneously released an EP under her own name which is a collection of Casablanca records cover versions, it includes a faithful interpretation of Summer’s slippery and melancholic “Working the Midnight Shift”. “In A Dream” is a record that may wear its influences heavily on its sleeve but the cluster of magnificent songs and the vocal dynamics honed between the two prevents it from falling into a potentially deep hole of nostalgia and tribute.

If their 2005 debut album was an accurate record of the post-electro clash, nihilistic and disco-damaged DFA early days and the follow up and homage of sorts to British synth pop and handbag house then this record is where the pair decide to reach back even further. There has always been a vivid and brattish clutch of songs that have been hard to ignore in The Juan Maclean’s back catalogue, screaming and shouting for attention and not fully formed. “In A Dream” has eliminated these kinds of distractions and is all the better for it; Nancy Whang is afforded full vocals on six of the nine tracks here and is having a ball in the process. Her voice is not that of a disco diva although frequently this is precisely what the sonics would appear to dictate. It has a flat and disinterested quality and still, somehow, considerable charisma, and Whang can interchange between dismal, withering betrayal and a warm optimism that dominates for example the gradually unfurling and uplifting ten minute closing track “The Sun Will Never Set on Our Love”. Tellingly this is their first album to feature just Nancy Whang as the cover artist, overshadowing a metallic bust of a physically absent Maclean.

“You Were a Runaway” has a choppy and to-the-point Grace Jones type pop structure. “Running Back To You” with its gorgeously padding synth swirls and reference to Imagination’s slinking 1980 hit “Body Talk” is the album’s only mid-tempo song and sees Whang softened but not entirely submissive. “Love Stops Here”, which may have the album’s strongest melody, puts Maclean upfront and sounds like a very good LCD Soundsystem song with washes of New Order guitar along with Whang’s glorious ‘do do do’ refrain popping up for the very last moments. “I’ve Waited for so Long” is a tight and confrontational “Don’t You Want Me”- styled trade-off between the two vocalists. It borrows the bassline from Cerrone’s “Supernature” but like so much of the material here the duo detail and layer the soundscape to the point where it isn’t pilfering but perfecting a sound that is, within the confines of this album, completely theirs.

Two of the most complete and satisfying songs, the aforementioned Moroder-indebted “A Place Called Space” and the penultimate track “A Simple Design”, both featuring a dominant Whang vocal, see The Juan Maclean finally solidify an effortless and endearing personality. Since “Less Than Human” the couple have spent a decade attempting to gel in a way that allows them both to share the lead, a hard feat indeed as Whang is not just a ‘front woman’ and neither is Maclean an invisible producer in the mould of, say, Goldfrapp. With Maclean cast in the role of an outsider and a muted and occasional vocalist to boot, you feel that he is now happier to concentrate on perfecting the world that surrounds the two and less inclined to push his voice to the front in a way that has read as self-conscious before. It is impossible to imagine him for example delivering the stand-off line ‘time after time, when what you’re hoping to find is not a simple design but a headache!’ from “A Simple Design” with the same brutish gusto as Whang does. Both roles are of equal importance and “A Place Called Space” sees The Juan Maclean arrive at their ultimate destination; confident, possessed and prepared to share it with us. We should think ourselves lucky.