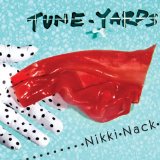

Tune-Yards – aka New England vocalist Merrill Garbus and partner in bass-playing crime Nate Brenner – have allowed some major pop producers, namely John Hill and Malay, access to their already established and almost aggressively individual sound. Concerns of a disaster in the making may ring out; their first album unbelievably lo-fi and the second self- produced – how would makers of albeit alternative but identifiable r’n’b pop affect the truly eccentric and self-sufficient band’s identity? Well, not as you much as you may imagine or possibly fear. There are changes of course as one would expect and also hope from any artist that has been producing music in excess of five years, but these are subtle and even, on occasion, welcome amendments made to the Tune-Yards manifesto.

Tune-Yards – aka New England vocalist Merrill Garbus and partner in bass-playing crime Nate Brenner – have allowed some major pop producers, namely John Hill and Malay, access to their already established and almost aggressively individual sound. Concerns of a disaster in the making may ring out; their first album unbelievably lo-fi and the second self- produced – how would makers of albeit alternative but identifiable r’n’b pop affect the truly eccentric and self-sufficient band’s identity? Well, not as you much as you may imagine or possibly fear. There are changes of course as one would expect and also hope from any artist that has been producing music in excess of five years, but these are subtle and even, on occasion, welcome amendments made to the Tune-Yards manifesto.

2011’s “Whokill” was an astonishing force of nature; it blew everyone and everything that stood in its path away but left Merrill Garbus drained and creatively arid. “Nikki Nack”’s opening lyrics tell of Garbus’ frustrations and the encouragement given to her by a stranger based only on her casual, overheard, singing:

‘You tried to tell me that I had a right to sing

Just like a bird has to fly

And I really wanted to believe him because he seemed

Like a really nice guy

But I trip on the truth when I walk that wire

When you wear a mask, always sound like a liar

I tried to tell him all the reasons that I had never to sing again

And he replied ‘You’d better find a new way’

Garbus’ wide eyed, exclaiming vocals – certainly soulful and often astoundingly powerful – sound pretty much the same on “Find a New Way” as they always did. The change then comes mainly from the songs themselves and Tune-Yards development as writers. Garbus has spoken about her love of sticky, ear worm- songs that attack the brain, embedded forever. One of the objectives she had for this album was to figure out how to write such hooks and incorporate them without compromise of creativity and individuality. Maybe this was the reason for recruiting the producers of, amongst others, Pink, Shakira, Alicia Keys and Christina Aguilera; John Hill and Malay are music specialists who understand how to navigate an artist towards the potential of a great melody. Along with Brenner, the band has again self-written the entire record and this objective of creating catchiness has, on the whole, been met, with many satisfying examples.

The first half on “Nikki Nack” is more convoluted stylistically than the second and also has a lower hit rate. “Water Fountain”, the album’s first single, squashes all of Tune-Yards characteristics and tics into one song. It’s a very tight squeeze; playground skipping rhymes, yelps and ‘yee- ha’s!’, clanging and clattering percussion, exhibitionist vocals and lyrics about a crumbling and under-funded neighbourhoods and a video that references Peewee Herman’s “Play House”. Ostentatious, wacky and be-jewelled, it’s not subtle and, after the initial and undeniable rush has worn off, it’s not enduring either. “Look Around” and “Time of Dark”, both slower tracks, feel longer than their playing time and “Real Thing”, which starts off brilliantly with staccato thrown verses circa “Writing on the Wall” era Destiny’s Child, ends in a tangle of voices and sonic muddle.

“Hey Life” chronicles an existence led too fast accompanied by anxiety and a pressure to cram as much as possible into every waking second; its drumming, synth prods and speed singing all add to the heightened feeling of panic with Merrill central to the ensuing chaos. It’s a minor track in some ways but one that is nonetheless thrilling and manages to avoid any cartoonish inclinations on a track where this could have been an easy temptation.

The strongest section of the album begins with “Stop that Man” which introduces a trio of songs where evidence of growth in song-writing and an ability to apply a more contained but ultimately more rewarding approach is clearly apparent. One of the continued aims of Tune-Yards has been to comment on social and left-leaning political issues with lyrics that are set against predominantly upbeat and dense dance rhythms and beats that imply a celebratory mood. Casual racism, gentrification and sexual harassment are all central themes here and “Stop that Man” questions racial assumptions based on media statistics and news reports and also personal experiences. The song succeeds mainly though by being part angular, glitchy electro clash experiment (it turns inexplicably and temporarily into Blue Monday/ Bobby O for forty-five seconds mid-song) and part glorious, singalong pop song. So if Garbus’ intention was to create a song serious in intention that you’ll also sing and dance along to, she has also again succeeded.

“Left Behind” and the downbeat but not depressing, smoothly r’n’b “Wait for a Minute”, probably the album’s best tune and performance, complete the trio and these moments are some of the finest in Tune-Yards discography to date. There is nothing that rivals the unruly, audacious and already ground -breaking “Gangsta”’ for example, here; the Tune-Yards of “Nikki Nack” are indeed more mannered but also more intricate with one beady eye placed on fine detail and songs that reveal themselves more slowly and reward generously over time. Claims of cultural appropriation, for they have been made, are surely overblown and only on the multi harmonies of the lullaby-like “Rocking Chair”, short and little too on the nose, does the intention grate. Other influences can also be heard, Laurie Anderson, Cyndi Lauper, Missy Elliott and Timbaland, Santigold, Big Boi, MIA and Neneh Cherry in particular all register at certain points but never once could you mistake Tune –Yards for anyone else. “Nikki Nack” may not shout its intentions as loudly as before but its power is found elsewhere, you’ll find yourself madly singing its merits – probably unaware and almost certainly with glee.

‘Return to form’ can sometimes be a cruel phrase when applied to an artist usually following a long period when attempts at a experimenting and self -expression are regarded as not working; when it’s finally time to ‘give the people what they want’, especially when the artist in question is finally happy with their new found creative freedom. It’s also a phrase which may have been overused in association with the Pet Shop Boys over the last decade or two. I’m reluctant to use it here as initially “Electric”, their twelfth studio album, feels more like one of their semi-regular ‘Disco’ excursions rather than a new album proper. There are only nine tracks, two of which are instrumental, with almost every track being at least 5 minutes long; there are no slow songs, but there is a ballad. But it’s much more than that, these are all new compositions, not remixes, and bears closest resemblance to 1988’s ‘Introspective’ which was an exceptional collection of long, newly-written at the time, dance-orientated songs. “Electric” also contains some of the most PSB-‘type’ songs the duo have released in a very long time and with Stuart Price’s bombastic, detailed and instantly gratifying production this is an album that fans who may have drifted away in recent years will feel instantly and overwhelmingly connected with.

‘Return to form’ can sometimes be a cruel phrase when applied to an artist usually following a long period when attempts at a experimenting and self -expression are regarded as not working; when it’s finally time to ‘give the people what they want’, especially when the artist in question is finally happy with their new found creative freedom. It’s also a phrase which may have been overused in association with the Pet Shop Boys over the last decade or two. I’m reluctant to use it here as initially “Electric”, their twelfth studio album, feels more like one of their semi-regular ‘Disco’ excursions rather than a new album proper. There are only nine tracks, two of which are instrumental, with almost every track being at least 5 minutes long; there are no slow songs, but there is a ballad. But it’s much more than that, these are all new compositions, not remixes, and bears closest resemblance to 1988’s ‘Introspective’ which was an exceptional collection of long, newly-written at the time, dance-orientated songs. “Electric” also contains some of the most PSB-‘type’ songs the duo have released in a very long time and with Stuart Price’s bombastic, detailed and instantly gratifying production this is an album that fans who may have drifted away in recent years will feel instantly and overwhelmingly connected with.

“Axis” is an instrumental, extended intro, sounding very much like of a mid-eighties TV theme, something butch, as imagined by Bobby O and Harold Faltermeyer; it’s warm and full sounding and is where the album title comes from. “Bolshy” follows, with its emphasis on the Russian Bolshevik rather than general stroppiness, and is the track which really launches the album with its house piano, familiar melody patterns and sarcastic attitude. Midpoint the vocal track sticks on the ‘O’ of Bolshio and a familiar cowbell sticks to the beat and acid house squiggles start to spiral out and take over. “Love Is a Bourgeois Construct” could have been a worry with the album peaking too early, an unwarranted concern as it turns out. With a filtered intro very much like Madonna’s “Hung Up”, also produced by Price, strings saw before a twee, archetypal British sample floats around, and then thump, we’re off. Like the best tracks on “Electric”, “Bourgeois” has a twin with an earlier PSB classic and in this case it’s the mighty “Left To My Own Devices”; if it doesn’t quite match the level of brilliance of that track then it comes pretty close. ‘I’m exploring the outer limits of boredom, moaning periodically, just a full time lonely layabout, that’s me’ is Neil Tennant’s admission as, in a heightened version of himself, he manages to refer to Tony Benn, Karl Marx and uses the word schadenfreude all in the same song. A male choir crashes in a la “Go West” and it’s this one track that both grounds and dictates the overall sound and scale of “Electric”.

“Fluorescent”, one of the best tracks, is moodier; minor in key with an ascending synth melody that constantly threatens to turn into “Fade to Grey” and containing some of the best lyrics on an album packed with them (‘I can’t deny you’ve made your mark with the helicopters and the occasional oligarch…every scandal has its price’) with one of the PSB favourite themes of international glamour and clandestine lives led at night continuing after they were first introduced on the couple’s debut album from 1985, ‘‘Please’. “Electric”’s non- ballad, ballad is the thumping, squally “Last to Die”, a cover version of a Bruce Springsteen song which I’ve never heard before but here sounds very much like a Pet Shop Boys original; pompous, sad, sincere and just a very good pop song.

Aside from “Bourgeois”, the two very big hitters are saved until last. “Thursday” is essentially “West End Girls”, sonically definitely, with Chris Lowe’s monotone chant of ‘Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday’ leading into a brilliantly realised, working class, blokey rap and middle eight by Example. Listen to the way he pronounces ‘memories’ for example (excuse pun); it was always about the details. “Vocal” is the most euphoric and obvious track on “Electric” and plays to many of the clichés of the current EDM craze with its big, cheesy, rave hook which is straight from 1999, see in particular Felix’s massive anthem “Don’t You Want Me”. But it’s the combination of the audaciousness of this sound coupled with the themes of nostalgia and narcissism (‘I like the lead singer, he’s lonely and strange….It’s in the music, it’s in the song, and everyone I hoped would be here has come along’) and also the subject of music itself that makes it such a success; it’s moving and it has history. The Pet Shop Boys have been making records like this for nearly 30 years; you can jump up and down to it and it will leave its mark somewhere deep.

So in 2013 the Pet Shop Boys sound an awful lot like they did whilst they were at their peak in 1988 and it appears as though it’s very much business as usual after it was strongly hinted that the business could finally be about to close down completely (last year’s “Elysium”). You could argue, and many will claim, that it’s the inevitable “return to form” then, but the PSBs form should not really be called in to account. All of their releases have merit, just in varying degrees, and their decision to do this seems a natural one; the whiff of cynicism is not detectable. In Stuart Price, Lowe and Tennant have found a producer who sounds like the lost third member and on “Electric” he has delivered his most on-the money, consistent production to date on some of the most accessible and immediate songs the duo have written in years. Whether or not it buys new fans, younger fans, is debatable and will remain to be seen but there are enough people who will rightly adore this sparking, intelligent and brilliant pop record and it does feel as though this album was made especially for them.